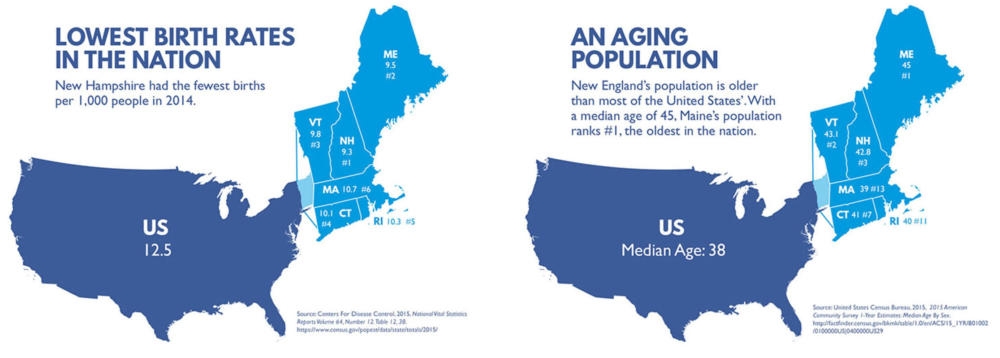

It’s hard to avoid the hand-wringing about aging demographics in New England these days. The region’s six states have the six lowest birth rates in the country. Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont have the oldest populations in the country, and Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts aren’t far behind.

These demographics leave the region desperate for young workers who can power businesses, pay taxes, and won’t dip into social security for decades.

New England’s business leaders and politicians are looking at any number of solutions, from putting classrooms in manufacturing plants, to giving tax cuts to Millennials.

Only in Maine, however, is immigration a major part of the public policy conversation.

Fewer births

Like many of the region’s elementary school principals, Becky Ruel knows more than she’d like to about New Hampshire’s declining birth rates. A decade ago, more than twice as many students attended Kensington Elementary School as do today.

“When I started three years ago, there were two third-grade teachers, two fourth-grade teachers, and two fifth-grade teachers,” Ruel says.

Today, the school is down to one teacher for each grade level.

The hallways at Kensington feel big and quiet. One whole room in the school is now dedicated to physical therapy, another to science and math projects, and yet another is designated for hands-on learning.

But while the school is making use of the extra space afforded by declining birth rates, this same problem keeps business leaders like Dana Connors up at night.

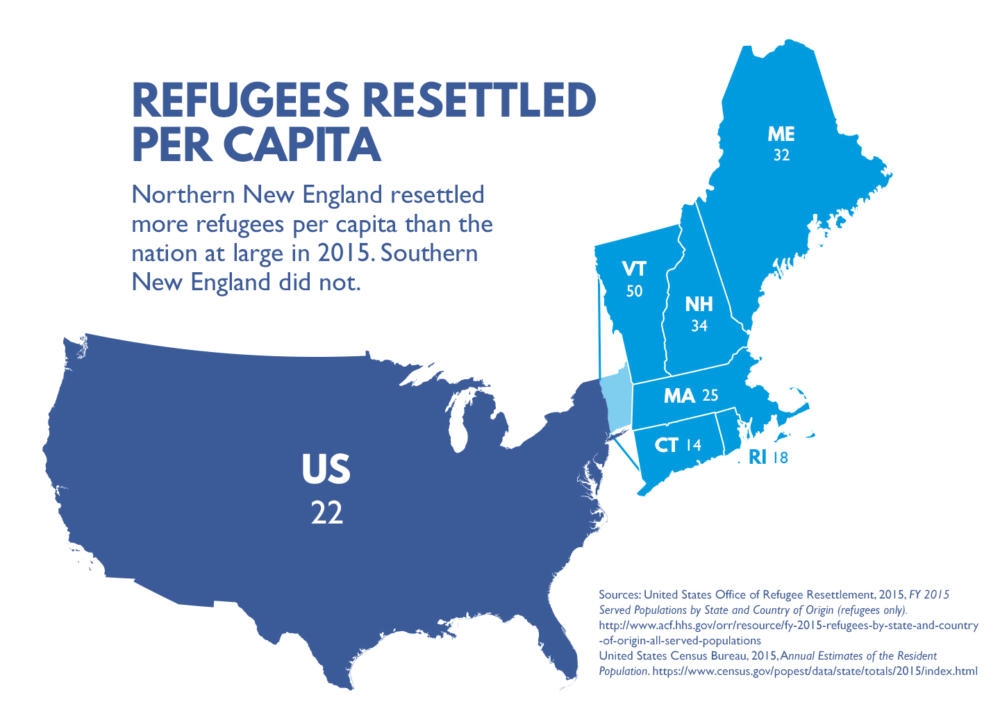

Connors is the president of the Maine Chamber of Commerce. When his team looked at the demographic trends, he said, “you found a very strong case to be made to attract the immigrant worker.”

As in other states, Maine’s business community is lobbying for programs to help Maine residents find good jobs in the state. But that won’t be enough to stem the shortage posed by declining birth rates.

One solution: Immigration

Connors and the Maine Chamber of Commerce recently released a report recommending policies to attract more immigrants to Maine. The report suggests expanding the New Mainers Resource Center that already exists in Portland, creating similar centers in Lewiston and Auburn, providing the centers with additional financial resources, and funding access to English classes and transportation.

Maine’s Gov. Paul LePage is famous for his anti-immigrant rhetoric, but that hasn’t stopped lawmakers from proposing legislation to fund more programs for new Mainers. At the local level, Portland and Bangor’s city councils are also working to establish centers for job preparation.

SIGCO, a glass and Metal fabricating company in Westbrook, Maine supports these efforts. Cindy Caplice manages Sigco’s Human Resources department. Even in December, when competition for workers is down, she says, “many people are still looking for help.”

That’s not the case at SIGCO, where about a third of the company’s workers are immigrants, many of them refugees. Thanks to them, Caplice says, her company has no openings.

Missed opportunities?

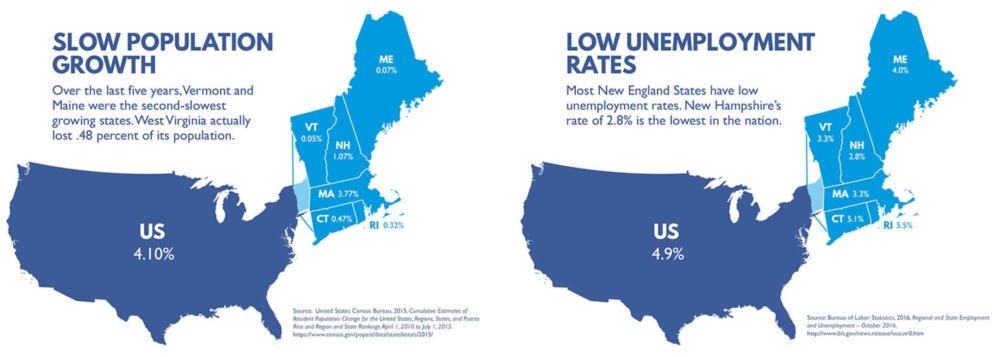

Across the border, New Hampshire has the lowest unemployment rate in the nation, which, combined with a shrinking population, leaves companies struggling to find workers. The state’s business leaders say little about immigration as a solution to workforce shortages. According to Amadou Hamady, businesses stand to benefit from immigrants who move here.

Hamady heads up a refugee resettlement program in Manchester. He says businesses should celebrate the role immigrants play in reversing New England’s economic trends.

“City officials, elected, need also to celebrate that,” Hamady says, “Because we’re keeping these industries going. But sometimes we don’t see a lot of that being said. I think it’s a missed opportunity.”

The Numbers

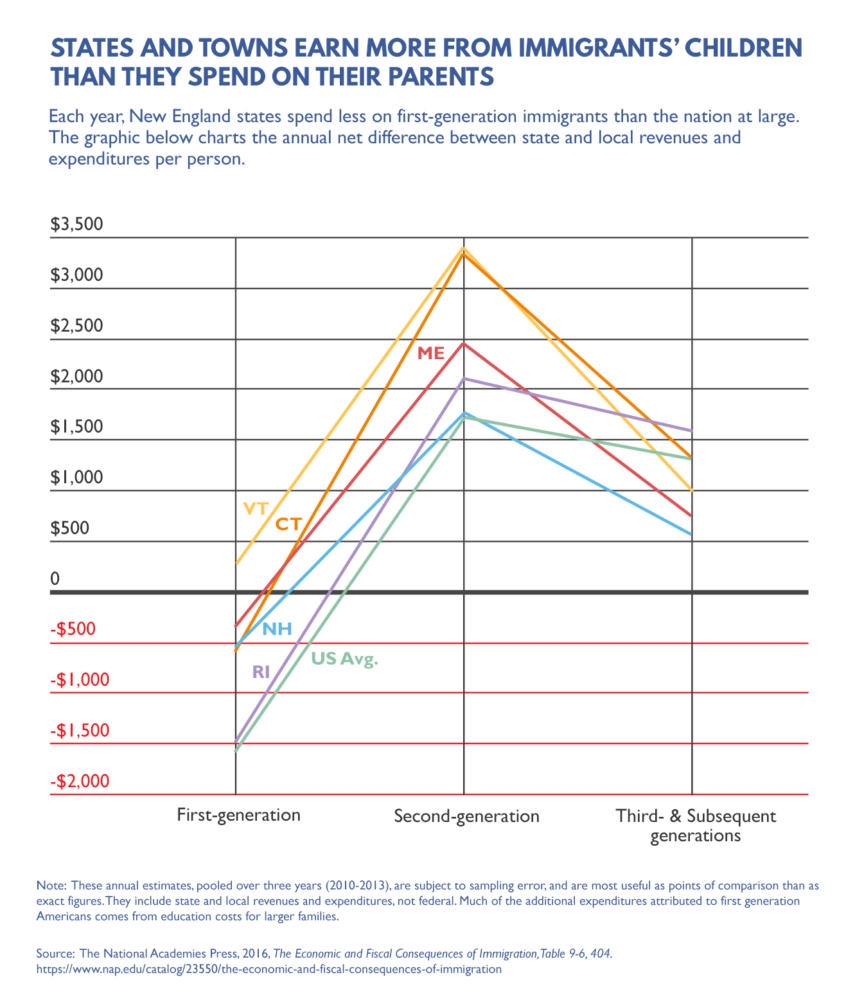

Research shows immigrants are economic drivers not just for businesses, but also for state and local budgets.

According to a report published by the National Academies Press, first-generation immigrants tend to cost states and towns more than they contribute in tax revenue. That’s mostly because of the cost of educating immigrants’ families. But, as economist Kim Reuben explains, “The second-generation individuals are both paying more taxes and using less services than both the first and the third” generations.

In fact, the children of immigrants contribute more to state and local revenues than the general population does.

Back at the Maine Chamber of Commerce, Dana Connors said he knows there’s a lot of confusion and concern around immigration policy.

But, he says, immigrants offer a lot of value, both economically and socially, so it’s worth it to keep a clear head.

This report is part four of a four-part series called “Facing Change.” Check out the earlier stories:

PART 1: Business Leaders Say Immigration Can Stem New England’s Workforce Shortage

PART 2: As New England Ages, Immigrants Make Up A Growing Share Of Health Workers

PART 3: A New England Community Prepares For The Arrival Of Refugees

The series comes from the New England News Collaborative, eight public media companies coming together to tell the story of a changing region, with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.