The city of Pompeii was destroyed during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Some may be familiar with the ancient site. It’s been a tourist destination for over 250 years. Not so familiar? Nearby Oplontis. That’s the focus of a new exhibition in Northampton at the Smith College Museum of Art.

On opening day of the exhibit, UMass Professor Laetitia La Follette was invited to speak to the crowd about some of the sculptures behind her.

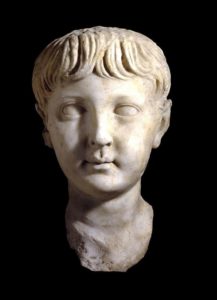

She offered details behind these artifacts, which give a glimpse into life in ancient Rome during the reign of Emperor Nero in the first century. One such artifact is the marble bust of a woman, who may be the mother of the Roman Empress Poppaea Sabina, Nero’s second wife.

“She dies under mysterious circumstances in 65 CE. The ancient authors say that actually she was kicked by her husband when she was pregnant, and she died of that,” La Follette said. “We know a great deal about her mother, and this portrait may be of her mother, who committed suicide in 47 CE.”

The Two ‘Villas’

The exhibit, which opened at the Smith Museum of Art on February 3rd, focuses on two adjacent Roman archaeological sites: what the museum is calling “Villa A” and “Villa B.” “Villa A” is a massive luxury villa once spread out along the coast of the Bay of Naples and believed to have been owned by the Empress Poppaea. The other is an industrial complex where the remains of 54 individuals had been found presumably sheltering in place to avoid fallout from the eruption.

More accurately, as Barbara Kellum explains, Villa B “is not a villa at all, but a wine emporium. Probably where they were waiting for a ship to come to the rescue that never arrived.”

Kellum teaches ancient Roman art and architecture at Smith College. She started coordinating this exhibit back in 2011.

Some of these people poignantly had nothing with them,” Kellum said. “Others had some of their most precious possessions…the kind of thing where you had no time and grabbed whatever you could and tried to flee.”

Much like a treasure trove of gold jewelry worn by a young woman found at the site. She was pregnant and in her early twenties.

Artifacts Sat In Storage

The stories this exhibit tells could very well have stayed buried.

The more well-known sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum were discovered hundreds of years ago, while the digging up of Oplontis only took place in the 1960s-70s. In 1984, the Italians ran out of money to continue working and placed the artifacts in storage.

Kellum said that when it came to relics of Vesuvius, “there were so many of them that the Museum of Naples has long been taken up with Pompeii and Herculaneum.”

So for decades, fragments and materials preserved from Oplontis sat in storage.

It was only until John Clarke and his team at the University of Texas at Austin started the Oplontis project in 2006 that much of this work was closely examined. This is the last showing of the exhibit in the U.S., which has been circulated by Kellum’s mentor, Elaine Gosda at the University of Michigan, with help from Italy’s Ministry of Culture.

‘A Real Treasure’

This exhibit offers a range of ancient objects preserved by the eruption: from luxury items like that gold jewelry, to household goods like silver spoons and terracotta lamps – giving a spectrum of class and lifestyle in Rome at the time.

“This contrast between the very wealthy and then the poor, I think, is definitely something very relevant to what we see in the world today,” said Taylor Anderson, a guest curator at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum.

Anderson was struck by an ornately decorated strongbox that would have been displayed in the main atrium of the empress’ luxury villa.

“Up above, there’s a couple of dogs – perhaps guard dogs – and um, a duck?” she said. “I don’t – I’m not sure why there’s really a duck there and then in the center there’s a head of a woman.”

Professor Kellum has an explanation for that. The strongbox is actually her favorite piece in the exhibit, originally fashioned sometime in the second century BCE.

“It has a very, very complex locking mechanism that you had to know how to manipulate,” she said. “It involves revolving that female head that’s up on top and shifting other elements on it in just the right sequence in order to unlock the strongbox.”

The complexity of the strongbox’s design speaks to just how much staying power these artifacts really have. Kellum said a better lock wasn’t designed until well into the 18th century.

Numerous items in the exhibit such as this are likely to inspire reflections on our shared history, as they did for David Brigham from South Hadley. I found him observing a marble sculpture of what may be a representation of Hercules.

“My father was in World War II and talked about being in Italy and seeing some of this stuff,” Brigham said. “It’s just a real treasure to be able to be here and see and hear about this history – it’s just fascinating.”

The treasures of Oplontis will be on view through August 13th.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly spelled Oplontis.