This Saturday marks the Lunar New Year, formerly known as the Chinese New Year. For commentator Grace Lin, it’s a holiday that comes with baggage.

As a child, I resented Chinese New Year. My Taiwanese parents celebrated with great enthusiasm. Other holidays, like Thanksgiving and Christmas, were treated as obligatory duties as well as with much puzzlement.

Why did it have to be turkey? And why did one have to go out in the cold just to hang up lights? Chinese New Year, however, made perfect sense! You ate pork dumplings to welcome in the new year and to wish for good fortune. You left your hair unwashed — you didn’t want to wash your luck away. You handed out red envelopes containing money — much more practical than a frivolous gift.

These traditions had been passed on for thousands of years, and I was embarrassed by them.

In fact, I was embarrassed by all Asian things. Growing up in a not-at-all-diverse suburb, I was always ‘the Chinese girl’ — easy to pick out in a crowd, but just as easily dismissed as nothing else but that. To be constantly on display, yet always invisible, filled me with deep insecurity. I wished I could erase the Asian part of my identity. But my physical appearance will never let me separate the Asian from the American.

And, strangely, I am now grateful for that. Because, in the end, I was forced to accept my appearance. And in doing so, I not only also accepted my heritage, but developed a great pride and a hunger to learn more about it.

Which is why now, having a daughter of mixed race, who does not look obviously Asian, is — for me — bittersweet. She might have a choice I didn’t have; if she wishes, she could shed the Asian part of being Asian-American. But I want her to choose to keep it.

How do I, one who is still learning about my heritage, share it with my child? And how do I share it so she sees it is worth keeping? These are questions I struggle to answer every day. I try to make her feel that the Asian part of her is special. I bought her a pink silk qipao and read Asian books to her. I go into her classroom to talk about Chinese holidays.

I have no idea if my efforts are working. But I keep trying. This year — the year of the rooster — my family is preparing for the New Year by wrapping a pork-leek mixture with dumpling skins, and crossing our fingers that they’ll be well made enough to fry as tradition dictates. But even if we have to boil them in a soup, we’ll eat them for dinner to make sure we get our good fortune and to treasure that which is deeply a part of us.”

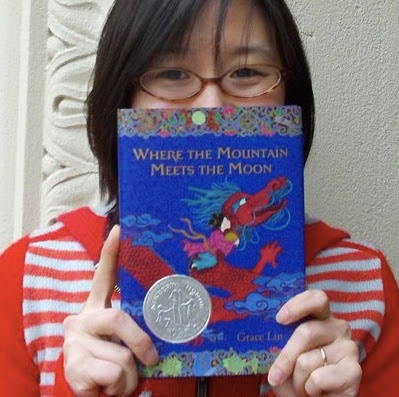

Grace Lin is the multi-cultural author and illustrator of more than a dozen children’s books, including the National Book Award finalist, “When the Sea Turned to Silver.” She lives in Florence, Massachusetts.