Emily Dickinson, the great American poet, was born December 10, 1830. Commentator and author Martha Ackmann lives a few miles up the road from Dickinson’s Amherst home, and often takes walks around town, planning her route to include a stop at Dickinson’s grave in West Cemetery — behind the Mobil station. What draws her attention is the tombstone, and also what’s been left on and around it.

Dickinson wrote 1,789 poems. Ten were published in her lifetime. Aside from a few forays to Boston and a trip to Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. , Dickinson spent her entire life — a reclusive one — in Amherst.

She’s buried in a plot with her parents, paternal grandparents and sister, Lavinia. There’s an imposing iron fence around the graves, a tribute to her father’s prominence as a town leader as much as her own posthumous fame.

There are other things too, especially atop the poet’s marker. Mementos: rocks, candles, pennies, scallop shells.

The head of Amherst’s Department of Public Works told me that several times a year a crew cleans the things left behind. Sometimes they find clothing, too, or a sleeping bag nearby. Homeless people occasionally sleep in the cemetery, he said, especially near Dickinson’s grave. It’s a ‘safe place’ for them. A harbor.

More than anything else, though, visitors leave notes at Dickinson’s grave. Lots and lots of notes. I unfolded one long strip of paper — soggy from rain the night before. It was a McDonald’s receipt for two orders of hash browns and a cup of coffee with cream and Splenda. On the back of it was this sentence: ‘I am thankful for the words you left.’

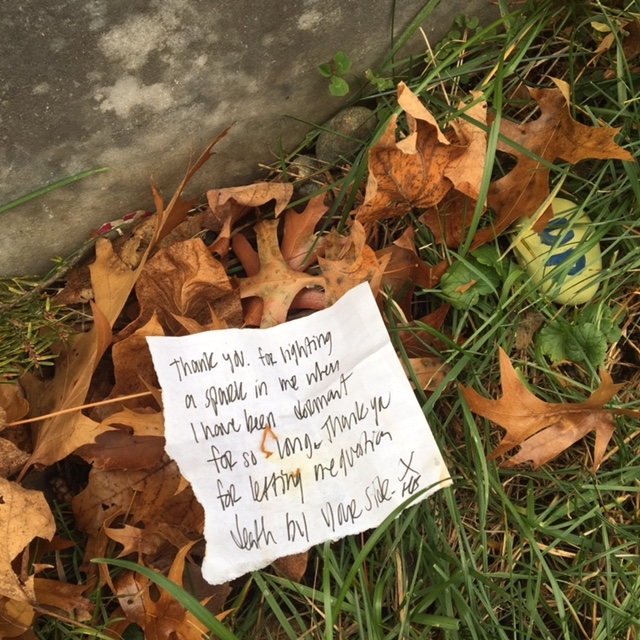

Another note was inside the gate, almost hidden among wet leaves: ‘Thank you for lighting a spark in me when I have been dormant for so long. Thank you for letting me question death by your side.’

Why does America’s greatest literary recluse continue to beckon us? She hardly seemed the type to engage with her own world, let alone ours.

In 1864, she wrote:

‘The Only News I know

Is Bulletins all Day

From Immortality.’Recently, I stopped by her grave and unwrapped another note. This time it wasn’t an expression of a reader’s gratitude. Someone had written Emily’s own words — speaking back to us.

‘In this short Life that lasts an hour

How much—how little—is within our power.'”

Commentator and journalist Martha Ackmann teaches at Mount Holyoke College and is writing a book about Emily Dickinson.