Massachusetts is one of about 40 states where someone who abuses drugs or alcohol to an extreme can be legally committed to a locked treatment facility. In most cases, a worried family member has to go to court to make that happen.

But one recent trend that has surprised even court officials is how many addicts are appealing directly to a judge — willing to give up their civil rights in exchange for some help.

Outside courtroom 4 at the Springfield Hall of Justice, a 33-year-old man was sitting upright on a bench, more alert than you might expect for someone who had just come off a heroin binge — after being clean for a month.

“Now I’m probably doing two bags,” he said. “And it’s getting me…high as a kite.”

The man didn’t want his name used, so we’ll call him A.L. He said he’s spending $1000 a week on heroin, scaring his family, scaring himself. That’s why he’s waiting his turn to ask the judge to lock him up in a treatment program that he can’t leave, far away from his dealers, even though that means giving up his liberty for up to 90 days.

If it’s going to save my life, then yeah,” he said. “Because it’s not going so good on the outside.”

A.L. is using a legal process known as Section 35 — part of Massachusetts law that allows a judge to order someone civilly committed to substance abuse treatment.

The law was enacted in 1970 to allow family members to force treatment onto children, spouses, siblings — back when alcoholism was the main problem. Now it’s mostly used for opioid abuse.

“Basically, it’s a good way to get clean,” said A.L. “Because if you try getting into these five or six-day detoxes, it takes forever. It takes a month to get into the place and if you don’t have the right insurance, they don’t want you. It’s a royal pain in the ass.”

Officially, you’re not allowed to ask for your own commitment; someone must petition for you, such as a close relative, a probation officer, or an emergency room doctor. But you can agree not to oppose it. A.L. even got a haircut to look good for the judge.

“If I don’t do this, I’m going to lose my freedom eventually anyway,” he said. “Eventually I’m going to get enough charges to the point where I go to jail anyway.”

Once in the courtroom, A.L. stood before Judge Michele Oimet Rooke.

His sister was the official petitioner, and a forensic psychologist testified that, because of his drug use, he was a danger to himself or others. That’s the legal standard.

“My client is in agreement to go to the treatment program in Brockton,” his lawyer, Maria Puppulo, told the judge. “He understands the seriousness of his addiction and he wants to get the help.”

With that, the judge ruled in favor of the commitment.

As a court officer put handcuffs on him and led him away, A.L. smiled and nodded towards his family.

That same afternoon, three other heroin users — in various states of coherence — were taken to detox in handcuffs, all of them willing.

Depending on what’s available, they would be assigned to a private treatment center connected to the court system, or — for men — a program at the state prison in Bridgewater.

‘That’s Not What Section 35 Was Created For’

In the past five years, court data show the annual number of Section 35 commitments has gone up by 40 percent — to about 8000 across Massachusetts.

They don’t break out the number of people who go voluntarily, but court staff say that number has also gone up. And that’s raised a question among some policy makers and advocates: Is committing yourself to a locked treatment facility, when you could just call up a detox program on your own, violating the spirit of the law?

“That’s not what section 35 was created for,” said Patrick Cronin, a longtime drug policy advocate who now helps run a treatment center in Quincy.

Cronin is also a recovering addict. Twelve years ago, he said, he was out of control, stealing checks from his parents to buy heroin, until they filed a petition to force him into treatment. At the time, he was furious.

“I was flipping out in court,” he recalled. “I was afraid of what life would be like without drugs.”

But today, he said that hearing saved his life. Which is one reason he wants to preserve the process for families who really need a judge to force their loved one into treatment. He’s concerned that too many voluntary commitments have created a bottleneck among treatment beds.

“That’s when you started seeing the judges make denials, on cases that they should not have been making denials,” Cronin said. “And the reason why was they were so backed up.”

That was one concern of state Senator Jennifer Flanagan of Leominster, who in 2014 led a legislative committee to investigate the rise in Section 35 commitments.

Flanagan says it became clear that many people could not find or afford regular treatment beds outside the court system.

If you’re an addict and you finally decide today is the day I want to go, you may not necessarily go through the hassle of calling every place and trying to get a bed, and calling your insurance company,” she said. “You might just go to court and get sectioned. Because you’re mandated a bed.”

It’s a bed the state pays for if insurance doesn’t — and often for a longer period of time.

State officials were not able to tell me how much Massachusetts spends on civil commitments, but Flanagan said she worries about the “cost of care, the cost of misuse of the system.”

Of course, what constitutes “misuse of the system” is open to interpretation.

‘It’s A Physical Compulsion They’re Experiencing’

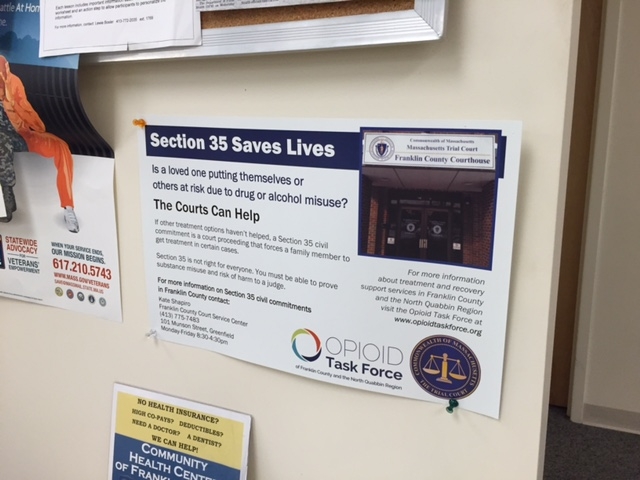

In Greenfield District court, signs throughout the hallways urge families to use Section 35 to access treatment. Judge William Mazanec presides over many of those cases, and said he first first noticed a dramatic rise in petitions a few years ago.

I met with my staff and said, ‘Make yourselves available. If someone walks in and says, “I have a heroin addiction, I’d like treatment, I need a commitment,” help them,'” Mazanec recalled.

If they could have gotten treatment some other way, he figured, they would have.

“When they come here and try to self-petition, it’s because they’re asking for me to use that process to force them into a situation where they can’t just walk out of treatment,” Mazanec said. “It brings people to that point. And you understand that you have a window of opportunity where they’re recognizing this. It is a physical compulsion they’re experiencing. You have to act quickly.”

The process doesn’t always run smoothly. Sometimes an individual will want to find out where they’ll be sent — a private treatment center or the prison — before agreeing to go. If it’s prison, they may want to stop the commitment.

That puts court officials in a bind, and frustrates state Senator Jennifer Flanagan.

“[The law] is to get someone out of imminent danger,” Flanagan said. “If you’re in danger, you’re in danger.”

Massachusetts health officials have recently started collecting data on how many people use the law on their own behalf. Leslie Darcy, chief of staff for the office of Health and Human Services, said they want to make sure the system is working the way it was designed.

If you have people who voluntarily want treatment, they don’t necessarily need to go to a place that’s secure, that has locked doors,” she said. “They can be in a less restrictive setting, receiving the care that they need.”

Darcy said, in the past year, Massachusetts has added more than a hundred new treatment beds specifically for civil commitment, as well as more detox beds in the community at large. She’s hoping that lessens the crunch in the courthouse.

But advocates say, until an addict or their family can pick up the phone, immediately get into treatment and know they’ll stay there long enough to have a fighting chance at recovery, the courts will remain a key part of the treatment chain.