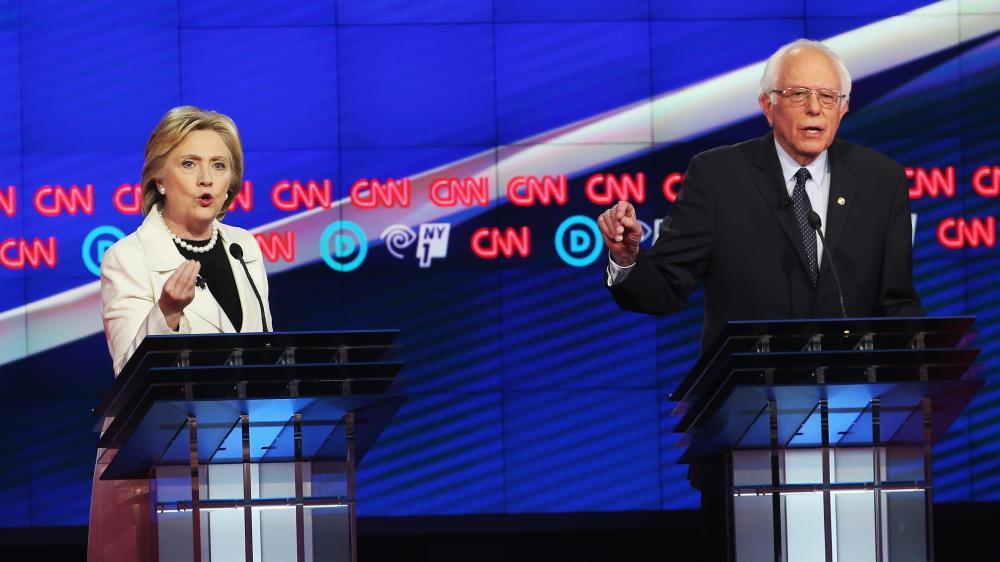

If Bernie Sanders surprises pollsters and confounds expectations in the New York primary on Tuesday, April 19, his backers and staff will trumpet the effect of his ninth debate with rival Hillary Clinton on the night of April 14.

They will say the relentlessly aggressive strategy Sanders pursued in the latest CNN debate, with its steady stream of attacks on Clinton, provided the defining moment in a long campaign for a nomination that remains up for grabs.

And that assessment will have some basis in what took place.

But if Sanders’ assault does not produce victory next week, then this latest Brooklyn faceoff may be the beginning of the end for Sanders’ remarkable long-shot run. And it may also be the last debate in either party in this historically long and lacerating contest for the major party nominations.

On this occasion, both Sanders and Clinton showed flashes of animosity bordering on contempt. When Sanders suggested Clinton’s 250-delegate lead was rooted in the deeply conservative Deep South, where he said she had “cleaned our clock,” Clinton angrily fired off a list of states she had won outside that region.

When Clinton said she had “called out” the big banks after the 2008 meltdown over mortgages, Sanders could not contain his sarcasm: “They must have been very upset by this,” he said, prompting howls of glee from his sizable contingent in the audience.

Throughout this event, the supporters of each candidate were loudly demonstrative, cheering not just at the end of answers but often at each sentence or phrase. At times, the raucous competition between the opposing contingents recalled competing grandstands at a high school basketball game.

They had more than ample provocation for their outbursts. Sanders put Clinton on the defensive regarding her vote on the Iraq War, her speeches to Wall Street firms and her late conversion to the $15-per-hour wage. He continued to hound her regarding the transcripts for her paid speeches to investment bankers.

But Clinton had Sanders back on his heels regarding his delayed release of tax returns, his remarks about NATO that recalled Donald Trump’s denunciation of members of that alliance, and his empathy for Palestinians in the Middle East conflict. The latter position is especially sensitive in New York.

Prior to the addition of this debate to the calendar, the Democrats had seemed satisfied with eight debates. But the Sanders campaign pressed for another meeting prior to the New York primary. The clear strategy was to profit from the string of caucus-state victories Sanders has won in the West since mid-March, magnifying his momentum even as it failed to reduce Clinton’s lead in delegates to any significant degree.

The debates have already reached an apparent end on the Republican side, where front-runner Donald Trump has declined to participate in anymore such events with remaining rivals Ted Cruz and John Kasich.

The Democrats’ debates began last fall, at which time Sanders offered a critique of Clinton that was relatively mild and muted and unlikely to disrupt the former senator and secretary of state’s march to the nomination. He famously declined to criticize her on the vulnerable points of her private email server and the fatal attack on American diplomats in Benghazi in 2012.

But since then, as the primaries and caucuses have evolved and Clinton’s lead among pledged delegates has remained stubbornly above 200, Sanders has chosen, or been forced, to adopt a different tack.

His campaign inner circle, which had long favored a more challenging approach, was able to make an urgent case: If you do not beat her in New York, where will you amass the delegates needed to overtake her in the pledged delegate category?

Polls show Clinton leading by double digits in the state she represented in the Senate. Polls also show her with similar advantages in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and Connecticut — all of which vote a week later, on April 26.

It should be noted that polls have been proven wrong in the past, especially where enthusiasm for Clinton on the primary voting day has been lacking in core constituency groups. Her double-digit lead in most polls prior to the Michigan primary in early March seemed to have vanished almost overnight when that state held its vote on March 8.

That could be why, in recent pronouncements, Sanders has repeatedly assailed Clinton’s fitness for the nation’s highest office by questioning her judgment. In general, he says, she has the resume to run for president. But does she have the judgment? He has returned to her vote for the use-of-force resolution that enabled President George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003. And he has made a major theme of her paid speeches to investment bankers.

These attacks on Clinton are consonant with Sanders’ larger indictment of the banking system, Wall Street, the financing of political campaigns in general and the presumptuous nature of the Clinton campaign in particular.

Both Clinton and Sanders argued in this debate that they would be the strongest prospective nominee against Donald Trump (or another Republican nominee) in November.

Sanders noted that he does better in the polls, meaning that in hypothetical matchups against the various Republican candidates, he scores better than Clinton. Clinton noted that she had received 2.3 million votes more than Sanders thus far in the primaries (and about half that many more than Trump), giving her a lead among pledged delegates far above what Barack Obama enjoyed when he defeated Clinton for the nomination in 2008.

Sanders has suggested that Clinton’s lead is based on her domination among the so-called superdelegates, who are entitled to vote at the national convention by virtue of their elected public office or party office. These delegates make up about 16 percent of the Democratic total. They have thus far shown a decided, even overwhelming, preference for Clinton.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))