The shutdown of Washington, D.C.’s Metrorail system for an entire day — 29 hours to be exact — for a safety inspection prompted a New York Times interviewee to say: “It’s the capital of the United States and one of the biggest business centers in the country. This is like a developing country.”

Actually, it’s not like a developing country, according to Aniruddha Dasgupta, global director of the World Resources Institute’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities, who is based in D.C.

It’s in a category all by itself.

“This is very unusual,” says Dasgupta. “It’s unusual for a large important city or any city to actually shut down the whole metro system. It’s not a normal way of functioning for any transit system.”

And that includes subway systems in countries that are part of the developing world: Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Beijing.

Besides, it isn’t fair to compare subway systems in the West with those in developing world cities.

“You would be amazed at how clean and fantastic the subway systems in China are,” Dasgupta says. “The one in Delhi is cleaner, brighter. But we have to remember these are relatively new systems. New York has been running its system for 100 years. It doesn’t look pretty, it’s dark, it’s rat-infested — but it works.”

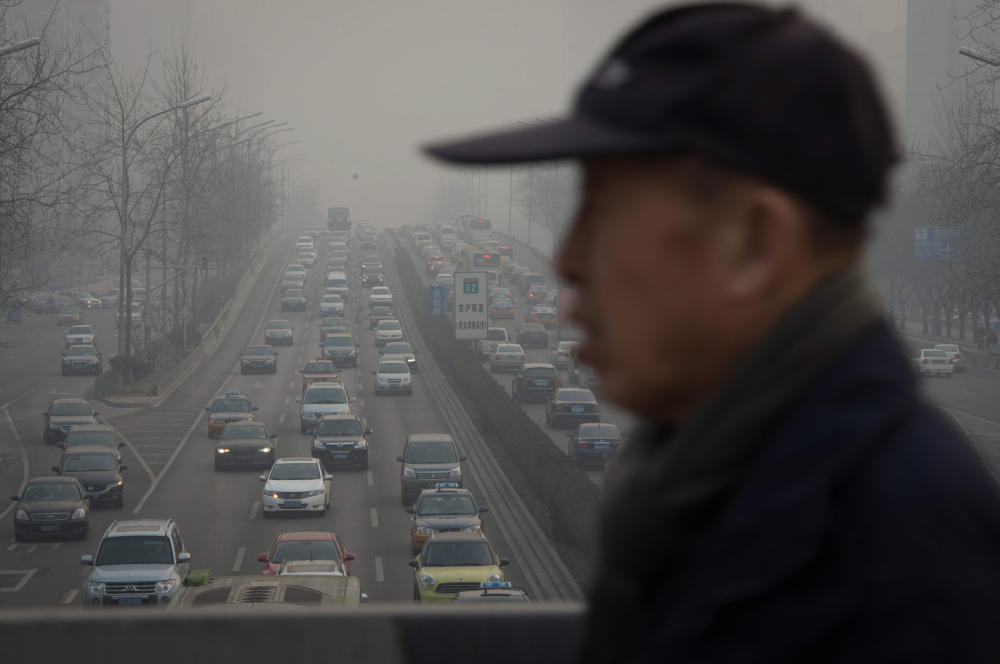

What’s happening in D.C. does touch on an issue that all systems struggle with: persuading commuters to give up the car for mass transit. To Dasgupta, that’s a critical decision if cities are to survive. Otherwise, streets will be choked with traffic and air will be polluted with car exhaust.

A shutdown like the one in D.C. sends people back to their cars. “When public transport becomes unreliable, people are going to say ‘Metro is not dependable,’ [and] they’re going to buy a car. That’s the opposite direction in which we should travel.”

And it’s definitely an issue in cities in the global south. As the developing world grows richer, more people are able to own cars in cities like Sao Paolo and Mumbai, he says. But the percentage of car owners in poorer countries still pales next to the U.S. It’s 6 percent in India, 17 percent in Colombia, 5 percent in Kenya. And 88 percent in the United States.

Countries across the globe are also pioneering a different kind of mass transit: BRT — bus rapid transit.

Buses get a bad rap in both the developed and developing world, Dasgupta says. They’re regarded as the vehicle of “poor people.” BRT systems aim to give the bus a better image. The vehicles are new and comfortable. There may be Wi-Fi. There are covered bus stations where passengers can wait, and the buses have a dedicated lane so they don’t get caught in traffic jams.

BRTs can’t carry as many people as subways can, Dasgupta points out. But they have definite advantages. Creating a BRT system from scratch is a lot cheaper than digging up a city to build a subway. And if a bus doesn’t work, you can take it out of service without shutting down the entire network as D.C. did.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))