The number of military veterans in the country’s jails and prisons continues to drop, a new report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows.

It’s the first government report that includes significant numbers of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — and the findings defy stereotypes that returning war veterans are prone to crime.

The data show that veterans are less likely to be behind bars than nonveterans. The study tracked an estimated 181,500 incarcerated veterans in 2011-2012, 99 percent of whom were male. During that period, veterans made up 8 percent of inmates in local jails and in state and federal prisons, excluding military facilities.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics began tracking the number of incarcerated veterans after the Vietnam War. In 1978, about 24 percent of prisoners were veterans. That number has fallen steadily since then, as the military switched from the draft to an all-volunteer force. In 1998, veterans had nearly the same incarceration rates as those who never served, and the number has been declining ever since.

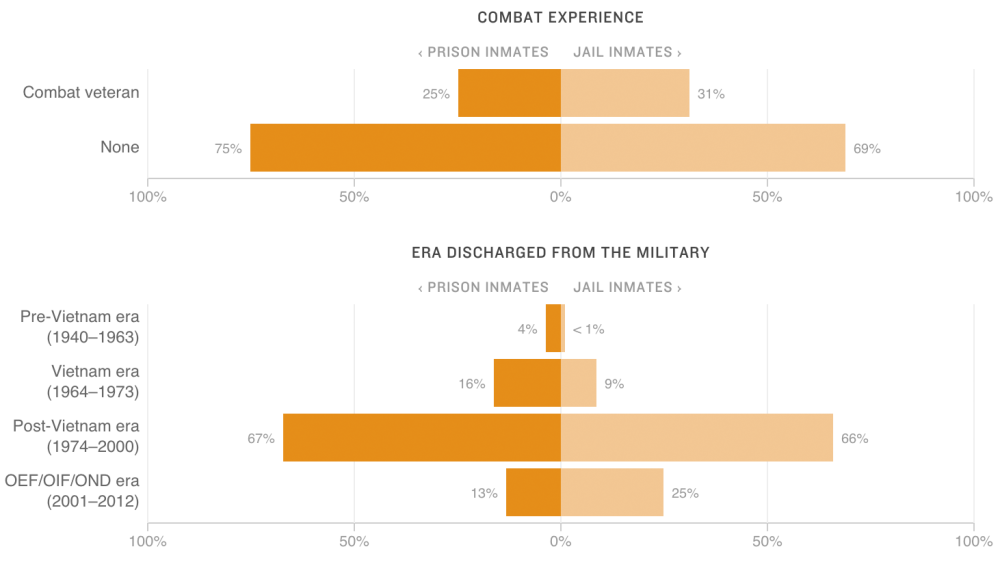

Those veterans in prisons and jails reported higher rates than civilians of mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Less than a third of veterans behind bars actually saw combat, but those who did also reported higher rates of mental health issues, according to the report.

On average, veterans doing time are almost 12 years older than nonveterans and are less likely to have multiple previous offenses.

The decline in the veterans prison population tracks national demographics. Across the country, the number of veterans is shrinking fast as the millions of vets from World War II and Korea reach their 80s and 90s, and Vietnam vets reach their 70s.

Advocates for veterans also credit the lower incarceration rate partly to increased services for returning veterans. For example, most states now have “veterans courts,” where veterans can get treatment for PTSD and drug abuse in lieu of jail time for certain crimes.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))