The number of people newly diagnosed with diabetes continues to decline after decades of increases that transformed what was once a disease of the old into a public health crisis that affects even children.

That’s not to say the crisis is over; 1.4 million people were diagnosed with diabetes in 2014, according to numbers released Tuesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s down from 1.7 million new cases in 2009, the fifth straight year of decline.

The numbers are going in the right direction, says Ann Albright, director of the CDC’s division of diabetes translation, “but we still have a long, long way to go.”

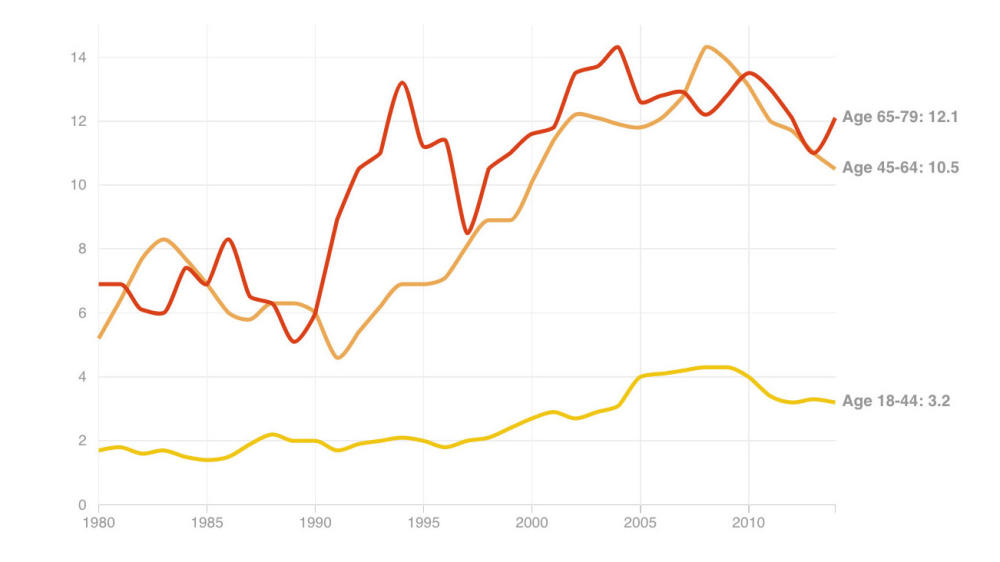

Indeed, the number of new cases each year are still triple what they were in 1980. And 29 million people, 9 percent of the U.S. population, have diabetes. Black and Hispanic people continue to be far more vulnerable. The number of new cases showed no consistent change among Hispanics from 2009 to 2014, and didn’t change significantly among blacks.

Diabetes increases a person’s risk of heart attack, stroke, blindness, as well as for nerve damage and circulatory problems that can lead to amputation.

“It’s not like we’ve beaten the epidemic, but it’s the first good news we’ve had in several decades,” says Dr. David Nathan, a diabetes researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He’s hopeful that if the trend continues, eventually the number of people with diabetes will start to decline, too.

The CDC data comes from a national survey that lumps together Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, even though they are very different. Type 1 is an autoimmune disorder that is usually diagnosed in childhood and is not affected by obesity. Type 2 is typically diagnosed in older people, and obesity and a sedentary lifestyle are key risk factors. It is much more common than Type 1, accounting for 95 percent of diabetes.

The big question, of course, is why are the numbers finally looking up.

Albright credits efforts like the National Institute’s of Health’s Diabetes Prevention Program, which showed that losing a modest amount of weight and getting more exercise sharply reduces the risk of developing diabetes in people at high risk. The studies were finished over a decade ago, enough time for the word to get out to doctors and the public, Albright says.

People are also more aware of the importance of healthy food, Albright says, and are starting to turn away from sodas and junk food. “We need to marshall our energy, our communities, in support of those healthy choices.” she says.

Targeting people at high risk has helped, says Nathan, who was a leader of the Diabetes Prevention Program studies. “It’s hard to argue that increasing activity levels and decreasing weight wouldn’t be good for everyone, but for those programs to be efficient you’ve got to target high-risk people,” Nathan says. With programs to test people and treat those considered to have prediabetes, “We now know we can do that.”

The nation’s rising rate of obesity appears to have plateaued, but it’s not declining the way new diabetes diagnoses are, notes Dr. George King, chief scientific officer for the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston. “This is a big change,” King says. “That means that something is changing faster than the obesity rate. Activity, sleep patterns, processed food — it’s probably a combination of all these things.”

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))