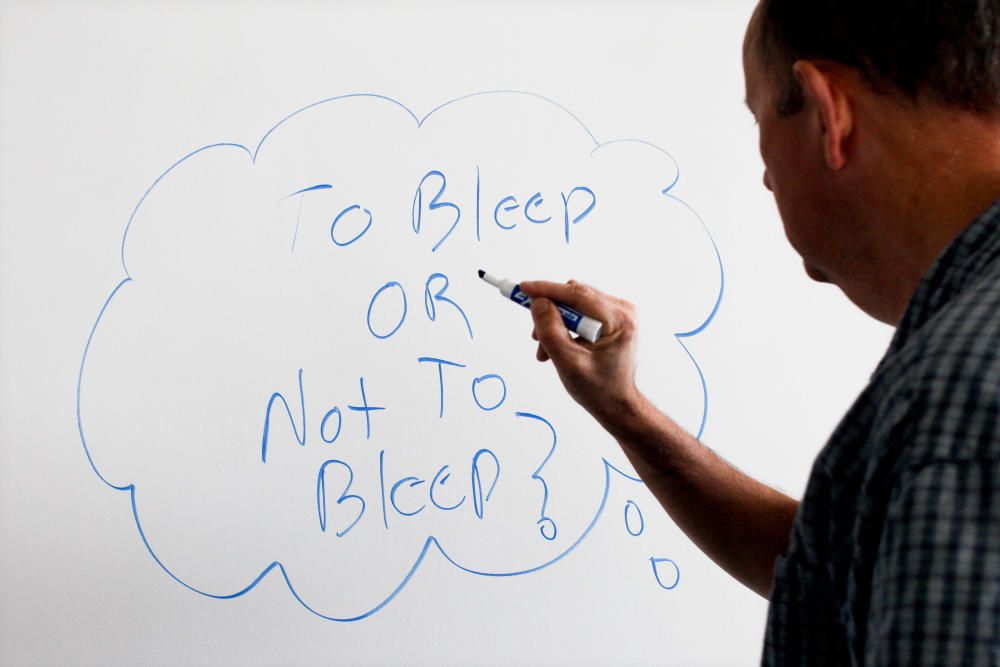

Editor’s note: The headline on this post tips our hand. But just to be clear, we’re discussing language that some readers don’t want to hear or read, even when it’s bleeped or not spelled out.

This question came up in the newsroom: Should an NPR journalist say during a podcast that someone’s an a****** if many people would agree that person is an a******?

The question wasn’t about a real person. It was about someone who would bet against his favorite team or would bet that his lover would say “no” to a marriage proposal.

The editors at NPR said “no,” the correspondent shouldn’t say that word. The policy is that our journalists shouldn’t use such language on the air, on NPR.org, in podcasts or on social media.

On Weekend Edition Saturday, we talk about NPR’s policy on the use of offensive language. Legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg joins the discussion, and makes a passionate case that the network’s policing of parlance goes too far. She doesn’t think NPR journalists should use profanity. “But we do, it seems to me, bend over backwards to do something we shouldn’t — which is to cleanse the news,” Nina says, when NPR “bleeps” certain words said by those who are in our stories.

To help frame the discussion, here are some key points about NPR’s policy:

1. It starts with respect.

“As a responsible broadcaster,” the policy reads, “NPR has always set a high bar on use of language that may be offensive to our audience. Use of such language on the air has been strictly limited to situations where it is absolutely integral to the meaning and spirit of the story being told. … We follow these practices out of respect for the listener.”

2. Things are different on the Web, but we want to be true to our principles.

The inspiration for this Weekend Edition discussion was a note this blogger sent to the staff. It read, in part:

“We don’t want to seem boring and out-of-step. We do want to sound like America. But, the bar that NPR journalists need to get over before using such language themselves has to be set incredibly high — so high, in fact, that it’s almost impossible to get over.

“We’re professional communicators at a major news organization. What we say and write in public reflects on NPR. No matter what platform we’re using or where we’re appearing, we should live up to our own standards. Yes, there’s more room in podcasts to let guests speak freely and for our journalists to be looser with their language. But it doesn’t mean NPR correspondents are free to use words or phrases in podcasts that they would never use on the air.

“We should always be the news outlet that revels in language. There are so many wonderful words. Use them!”

3. The decisions are made by NPR’s journalists.

Sometimes, NPR’s editors decide to put offensive language on the air because it’s an important part of a story. For example, when correspondent Eric Westervelt was traveling with U.S. Army forces during the Iraq War, the troops came under attack. His microphone caught the sounds, including a soldier telling a man to “get the f*** under the truck.” That went on the air, unedited and unbleeped. It met NPR’s test of being “vital to the essence of the story.”

Of course, the FCC regulates public airwaves and may takes steps to fine broadcasters that put obscene or profane language on the air. The commission’s guidance to broadcasters includes the warning that “ineffective bleeping” — letting even part of an objectionable word be heard — might be cause for a fine.

No public broadcaster could argue that it ignores the FCC’s guidance. Lawyers are consulted on these issues. But responsible broadcasters have journalists making the final decisions.

Mark Memmott is NPR’s standards and practices editor. He co-hosted The Two Way from its launch in May 2009 through April 2014.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))