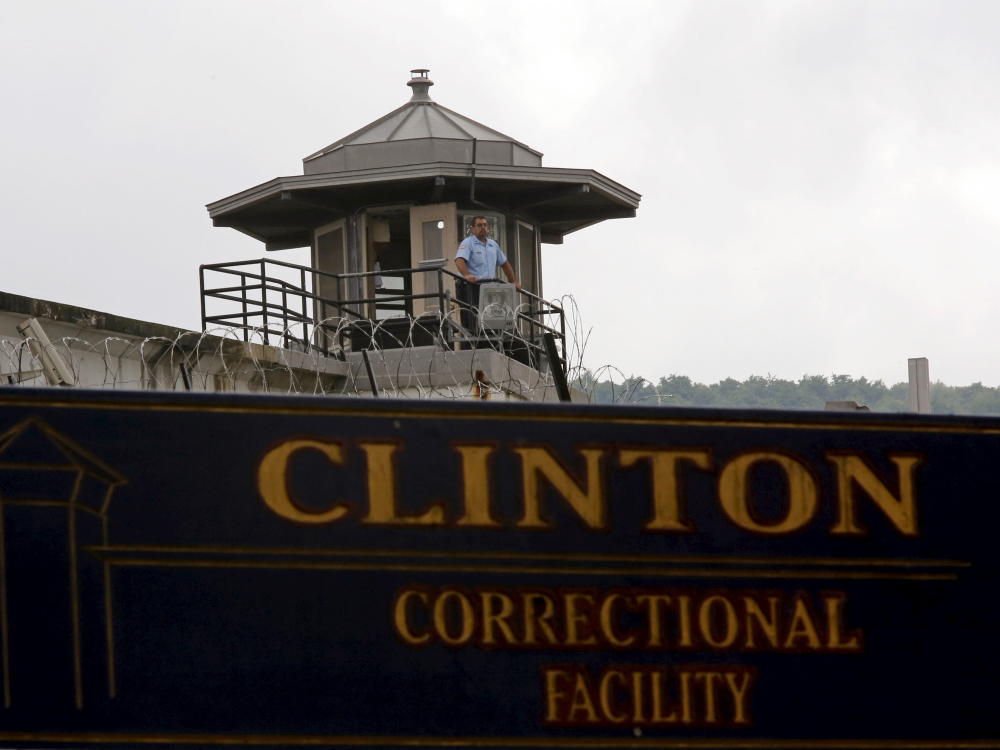

The first time I went inside Clinton Correctional Facility was more than a decade ago.

I was there to do a story about the architecture and history of this maximum security prison, built in the Adirondack Mountains in northern New York in the 1840s. It was a rare glimpse of a world and a culture few people ever see.

When two inmates escaped from Clinton a week ago, I listened back to that story and I found this moment, in which I described the scene inside: “Everywhere we go, prisoners are handling knives and power tools.”

Even then, that detail kind of freaked me out.

As the manhunt continues, authorities are still trying to sort out exactly how two convicted murders were able to dig their way to freedom. But Richard Matt and David Sweat used some kind of powered saw or cutting tool to cut their way through a steel wall and a steel steam pipe before escaping through a manhole cover.

On Friday, state police arrested Joyce Mitchell, a worker at the prison accused of helping the men. There have been no confirmed sightings of the two inmates.

There are a lot of questions about how they got that equipment. The truth is, inmates in New York prisons work with tools all the time.

“Any of the institutions are like that,” says Peter Light, who worked as a guard at Clinton Correctional Facility for three decades. Light, now retired, says using inmates to help with maintenance work is a cost-effective way to keep old prisons running.

“The maintenance is so large, so big, by using the inmate, you know, they can take care of things, keep it up better,” he says. “Yes, a lot of things can happen during that period of time.”

He means that inmates have a lot of access to equipment and supplies, and they also pick up a lot of information about how the prison works, the design of utility areas and the layout.

Another thing I learned during my three trips inside Clinton: Inmates have a remarkable amount of time and freedom to share information with each other.

During one of the tours, veteran corrections officer Gene Palmer led me to the vast North Yard, a sprawling part of the prison that is mostly controlled by inmates.

This part is so weird, it’s a little hard to describe. Inmates who don’t make trouble are allotted little pieces of land, called “courts.” That’s their turf.

“Looks crude, but it works very well,” Palmer said. “They have gardens. We have expensive sides; we have nice real estate here and we have poor real estate here.”

Inside their courts, individual prisoners can make gardens or set up private recreation areas or keep barbecue grills. Imagine a tailgate party a couple of football fields wide plunked down inside a maximum security prison, and you sort of get the idea.

“Over here, we have all the Italians, they’ve got the money, they get the nice courts over here,” Palmer said on my tour. “On the wall over here, there’s a man, he’s a convict here — I believe he killed his wife — and he’s got the best court up on top.”

The way Palmer described it, this huge area of the prison is divided into a pecking order along racial lines and among different organized gangs.

More than a decade after that interview, the North Yard is still in place, part of the fabric of the prison’s culture. Light, who is now Clinton Correctional Facility’s historian, says giving inmates that kind of autonomy has mostly worked well.

“It started in and the inmates enjoyed it,” Light says. “It was like an honor to be able to cook out in the yard and stuff like that. Over the years it just got bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. It ended up being a way that [the guards] could control things.”

It gave prisoners an incentive to do their time here without causing trouble. But now, Light says, a lot of questions will be asked — about the kinds of work inmates do and whether these old prison traditions made it easier for Matt and Sweat to hatch their escape.

New York prison commissioner Anthony Annucci says guards are now conducting an inventory of all the tools in all the state’s correctional facilities.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))

Transcript :

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Still no confirmed sightings of the two murderers who escaped from the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, N.Y., last week, but police have arrested a female employee suspected of helping the men. Authorities are trying to figure out how they managed to break out of a maximum-security prison. North Country Public Radio’s Brian Mann takes us inside that prison.

BRIAN MANN, BYLINE: The first time I went inside Clinton Correctional was more than a decade ago.

(SOUNDBITE OF PRISON GATES LOCKING)

MANN: I was there to do a story about the architecture and history of this prison, built in the Adirondack Mountains in the 1840s. I listened back to that story, and I found this moment describing the scene inside.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

MANN: Everywhere we go, prisoners are handling knives and power tools.

Even then, that detail kind of freaked me out, and now power tools have become a big deal here. Richard Matt and David Sweat used some kind of powered saw or cutting tool to cut their way through a steel wall and a steel steam pipe before escaping through a manhole cover. There are a lot of questions about how they got that equipment, but the truth is, inmates in New York prisons work with tools all the time.

PETER LIGHT: Any of the institutions are like that.

MANN: Peter Light is retired now, but he worked as a guard at Clinton Correctional Facility for three decades. He says using inmates to help with maintenance work is a cost-effective way to keep these old prisons running.

LIGHT: The maintenance is so large and so big that they actually – by using the inmate, you know, they can take care of things, keep it up better. Yes, a lot of things can happen during that period of time.

MANN: He means that inmates have a lot of access to equipment and supplies. And they also pick up a lot of information about how the prison works – the design of utility areas, the layout.

Now here’s another thing I learned during my three trips inside Clinton-Dannemora – inmates there also have a remarkable amount of time and freedom to share information with each other. During one of the tours, veteran corrections officer Gene Palmer led me to the vast North Yard. It’s a sprawling part of the prison that inmates mostly control.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GENE PALMER: It looks crude, but it works very well. They have gardens. We have expensive sides. We have nice real estate here and we have poor real estate here.

MANN: This part is so weird, so crazy, that it’s a little hard to describe. Inmates who don’t make trouble are allotted hundreds of little pieces of land called courts. That’s their turf. Inside their courts, individual prisoners can make gardens or set up private recreation areas or keep barbecue grills. Imagine a tailgate party a couple of football fields wide plunked down inside a maximum-security prison and you sort of get the idea.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

PALMER: Over here, we have all the Italians. They got the money. They get the nice courts over here. On the wall over here, there’s a man, he’s a convict here – I believe he killed his wife – and he’s got the best court up on top.

MANN: The way Palmer described it, this huge area of the prison is divided into a sort of pecking order along racial lines and among different organized gangs. And more than a decade after that interview, the North Yard is still in place, part of the fabric of the prison’s culture. Retired correction officer Peter Light, who’s now Clinton Correctional Facility’s historian, says giving inmates that kind of autonomy has mostly worked really well.

LIGHT: It started in and the inmates enjoyed it. It was like – like an honor to be able to cook out in the yard and stuff like that. And over the years, it just got bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger, and it ended up being a way that they could control things.

MANN: He means a way that the guards could control the inmates, giving prisoners an incentive to do their time here without causing trouble. But now Light says a lot of questions will be asked about the kinds of work inmates do and whether these old prison traditions made it easier for Richard Matt and David Sweat to hatch their escape. New York Prison Commissioner Anthony Annucci says guards are now conducting an inventory of all the tools in all the state’s correctional facilities. For NPR News, I’m Brian Mann in northern New York. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.