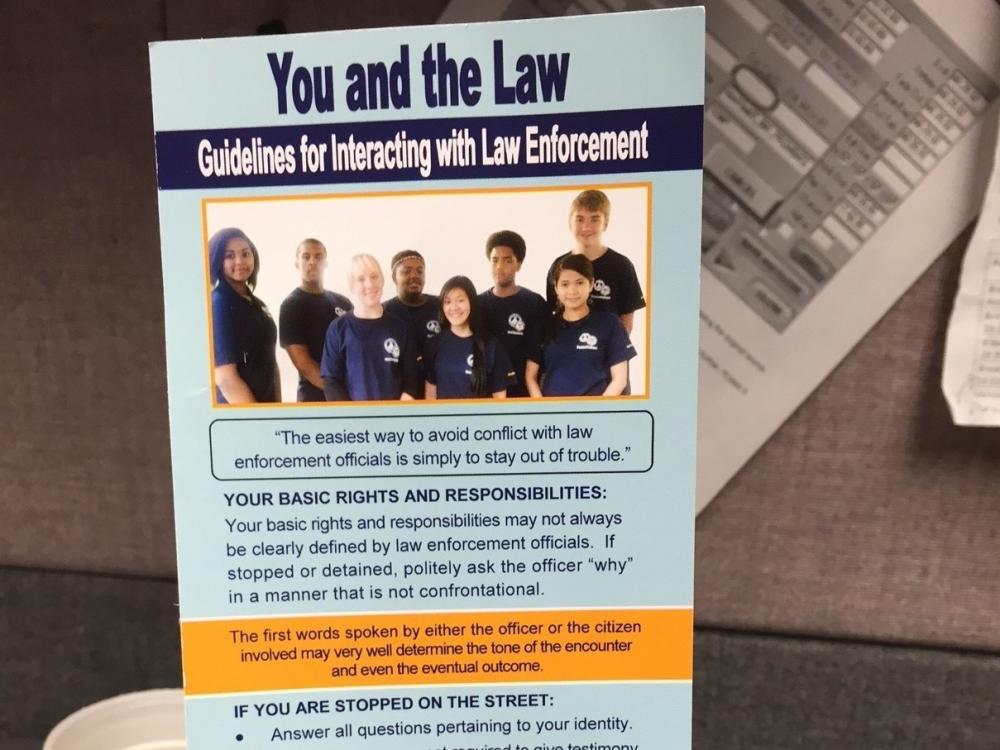

This week, every middle and high school student in Akron, Ohio, is getting a glossy, two-sided card giving them suggestions for dealing with police.

It’s a collaboration between an anti-violence youth group and the city’s police department.

The “You and the Law” cards begin with the big picture: Stay out of trouble. And then a rapid succession of 15 points — control your emotions, answer questions about your identity, put your hands on the steering wheel in plain sight.

The back of the card advises students to report police misconduct and includes phone numbers to call.

The youth group is known as Akron PeaceMakers. Member Devin Clark says it raised $1,500 to print 50,000 of the cards.

“When they get put in the situation, they’re going to look back at that card and be like, ‘Wow. You know, that helped when I actually read that.’ It’ll put them in a better position,” Clark says.

The cards are getting lots of praise from adults, but they’re now heading out to a tougher audience.

At Firestone High School on the city’s northwest side, the reaction is largely one of interest, with some debate over the responsibility of officers in encounters.

Student Rachel Cooke says it’s important that the cards recognize that police can be the transgressors.

“I’m not saying that all cops are bad, but there are cops that are drunk on their power, I would say. So I think that it holds them responsible so they can stay in line,” Cooke says. “They have to obey the law just like we do.”

In a quieter spot across from the cafeteria, Ryan Hall says he expects and welcomes the debate — better in a high school cafeteria than on the street.

“This is almost a preventative measure,” Hall says. “In many cases it was a small situation that has escalated to end up being a much larger situation.”

The idea for the cards came from a meeting in December, soon after police in nearby Cleveland shot and killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice on a playground.

Billy Soule is Akron’s liaison with the PeaceMakers. He says the kids wanted to see more than protests.

“We were hoping that someone within the community would say, ‘We need a mechanism to tell our kids what to do,’ ” Soule says.

So the kids did it themselves.

Though some argue the cards go too far in supporting the police point of view, these kids disagree. They say it was crucial that the cards also include advice to document and report police misconduct.

Ryan Hall says it’s a matter of letting people know they have options. “People can feel as if they’re powerless against police because they are the police — they’re put in a position of authority,” Hall says. “Instead of cussing him out, I can just say, ‘OK. Let me calm down,’ and then at a later time, call the police station.”

Willa Keith, a retired Akron police sergeant who works with the group, says it’s about building trust.

“We are all working for the same goal. We want peace in the city, we want harmony, we want to live the best lives that we can,” Keith says.

The Akron group plans to eventually distribute the cards to adults and to possibly extend the program internationally.

Gary, Ind., Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson, who chairs the U.S. Conference of Mayors Working Group of Mayors and Police Chiefs, says mayors across the country are desperate to find ways to bridge police-citizen divides in their communities — and she and others are looking at this approach as one way to do that.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))