“Pigeon: It’s what’s for dinner.”

That might sound strange to us, but it could have been uttered by our great-grandparents. Baked into pot pies, stewed, fried or salted, the passenger pigeon was a staple for many North Americans.

But by 1914, only one was left: Martha.

Named after Martha Washington, she lived a long life at the Cincinnati Zoo until 1914. The bird, now on exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, was a celebrity.

“There’s been a website up for a long time saying, put Martha back on exhibit. there are just that many people who care,” says Helen James, the museum’s curator of birds.

After years locked inside a metal cabinet, Martha is now perched on a branch, red eyes peering over her shoulder at museum-goers.

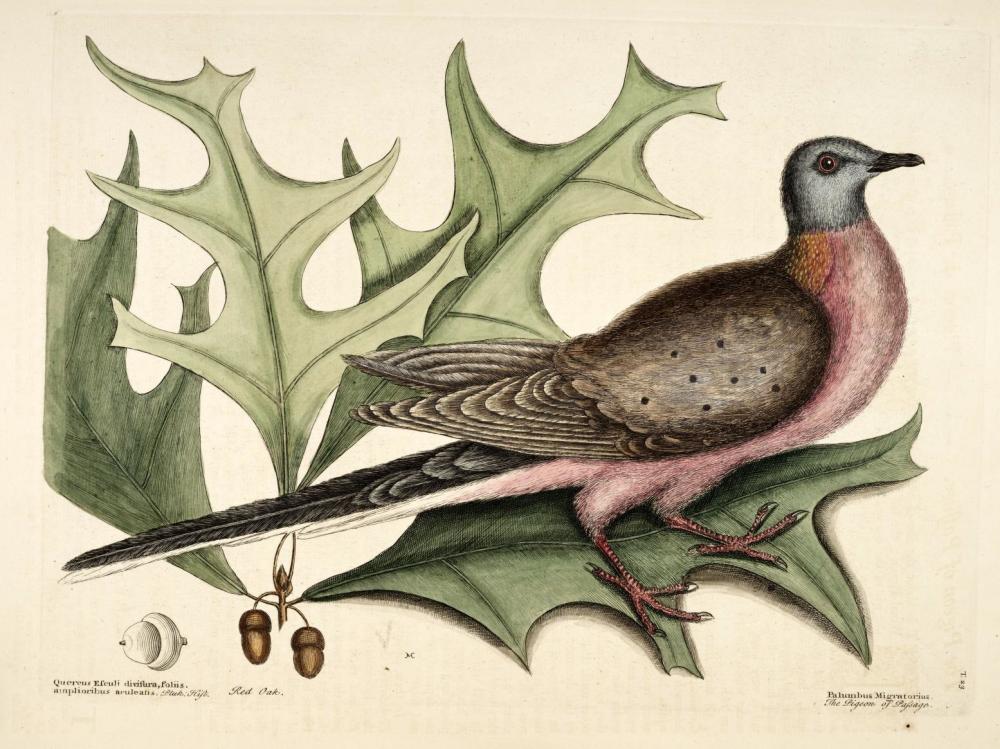

“Unfortunately, she’s rather drab-looking for a larger than life bird,” says James.

Despite the brown, tousled feathers, this bird was — and is — an icon. Her stuffed body has been flown first class all over the country. Songs have immortalized her.

Why the obsession with this one bird? James says a lot of animals have gone extinct, but it’s rare to be able to go to the zoo and look the last one in the eyes.

“There she was alive, you could go and see her. And you could know, when she dies, there goes the species,” James says. (A group of scientists wants to bring the passenger pigeon back from extinction, but they haven’t yet).

The passenger pigeon’s demise was dramatic. According to Joel Greenberg, who just wrote a book about it, their flocks used to darken the skies of North America. One report from Ohio in 1854 began when people noticed strange clouds forming on the horizon.

“As time went on it became clear that those clouds were birds,” says Greenberg. “And as more time passed, they were plunged into darkness. People who had never seen the phenomenon before fell to their knees in prayer, thinking the end times had come. The down-beating of hundreds of millions of wings created drafts. People were cold.”

The passenger pigeons’ tendency to cluster in such staggering numbers — in the millions — was their Achilles heel.

At pennies a piece, they were the cheapest protein on land. During migrations, so many would line the trees that sometimes branches would snap right off.

“Despite being the most abundant species, almost all those individuals could be in just a few major flocks at one time,” James says. “And so, if you could locate those major flocks, that made the species very vulnerable because you could harvest them intensively all at once.” And make a lot of pigeon pot pies, adorned with pigeon feet to show what was inside.

Hunters communicated by telegraph to locate the massive flocks, and then shipped them off by the barrel. Eventually, only Martha remained.

As the story goes, she lived to be about 30-years-old — decrepit for a pigeon. When she was found one day lying on the bottom of her cage, her body was immediately encased in a 300-pound block of ice, shipped to the Smithsonian, and stuffed for immortality.

In part because of Martha, in 1900 the U.S. passed the first federal law protecting wildlife, and much later the Endangered Species Act. But if you think we’ve learned our lesson, Greenberg says, think again.

“The depletion of the oceans is going on now. No country controls the open seas, so nobody can impose limits,” says Greenberg.

Like the passenger pigeon, cod and bluefin tuna were once abundant, though overfishing has made their populations vulnerable.

You can only guess what Martha would think, red eyes now glaring out of her glass case.

For the food history buffs, here’s a pigeon pot pie recipe from the 1800s:

“The to make a pot-pie, line the bake-kettle with a good pie-crust; lay in your birds, with a little butter on the breast of each, and a little pepper shaken over them, and pour in a tea-cupful of water — do not fill your pan too full; lay in a crust, about half an inch thick, cover your lid with hot embers and put a few below. Keep your bake-kettle turned carefully, adding more hot coals on the top, till the crust is cooked. This makes a very savoury dish for a family.”

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))