Inside one in a series of abandoned homes along a blighted block of Detroit’s Brightmoor neighborhood, filmmaker Tom McPhee walks through the remnants of a life — broken furniture, scattered knickknacks, and a flooded basement.

“This is fresh water that’s coming into the basement here,” McPhee points out. “All of that plumbing has been ripped away ’cause someone found a value in it, so they don’t care that it’s running. This is all over the city.”

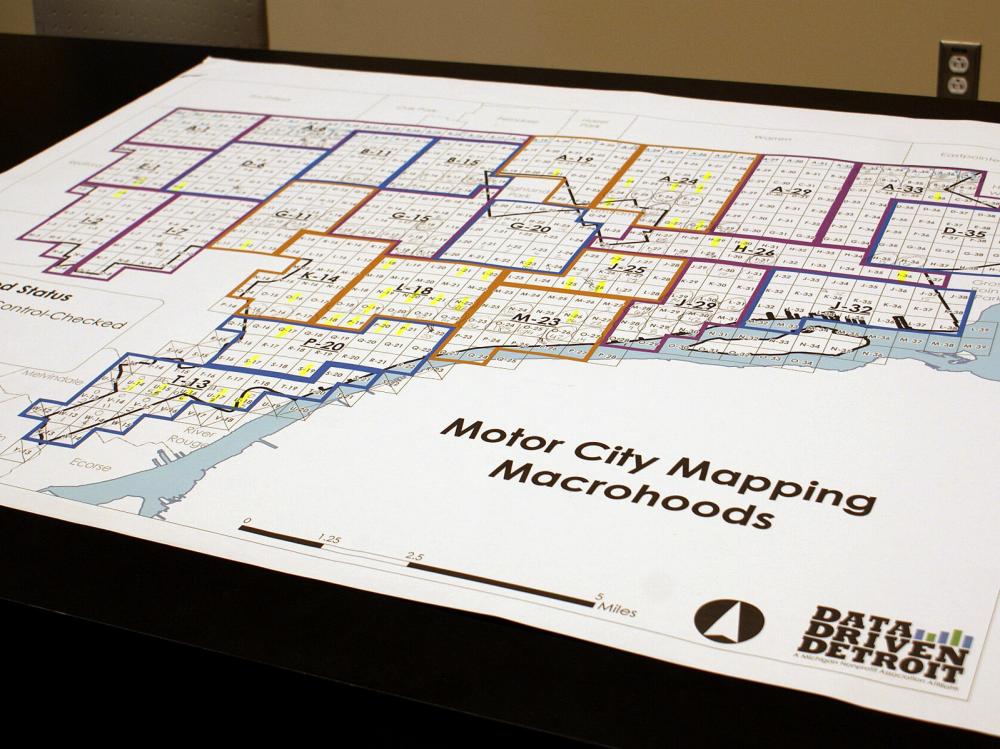

People like him help catalog blight in Detroit, but the sheer size of this city makes it hard to pin down: Detroit has 380,000 parcels of land stretched across 139 square miles — so many parcels that its antiquated computer system can’t keep up.

Last fall, White House officials created a Blight Task Force here in partnership with some private foundations, to determine just what property is salvageable among the estimated 80,000 abandoned buildings.

Now that information is pouring into a long room with dozens of people poised over laptops — a White House Situation Room-style mapping area with computerized images of all buildings in the city, and outlines of what should be done with them. This is “Mission Control.”

A map of Detroit covers one table. It’s replicated on the laptop screens and overlaid by a computer grid of the city. Blue dots represent surveyors out in the field, and they’re all over the city right now.

Lauren Hood works with Loveland Technologies, a company that developed a new way of mapping Detroit. They call it “blexting” — sending teams throughout the city to text pictures and descriptions of blight to a database. Hood says that in a few months, that data will be available as an app for anyone to access, or correct.

“People that actually live in the neighborhoods can respond to what’s been said about their neighborhood, and add to it or change it or update it,” she says. “They can have the power.”

Nearby, supervisor Mark Weaver remembers meeting residents whose initial suspicion quickly changed to hope once he described the project’s goals. He says the feeling of despair in these neighborhoods can be palpable.

“You’re seeing people who just gave up: They moved away, they gave up their homes,” he says. “And it becomes like a domino effect, because once all of your neighbors begin moving out, then you think, ‘Why should I stay here and maintain my home when I’m surrounded by blight and terror?’ ”

Detroit officials spent decades trying to tear down such homes, but each demolition costs between $5,000 and $10,000. The mapping project’s manager, Sean Jackson, says the new database will help them better use the scarce funding by compiling information that the city and county departments’ outdated computers could never integrate.

“And a lot of times they might own a couple properties next to each other, and they just don’t know that they all own a house on the same block,” Jackson says. “So now we can actually show them, ‘Hey, all four of you guys, all four different departments, you all have property on this street. If you’re going to send in a demo crew, instead of sending them in four different times, why don’t you all put your properties together and do all four of them at the same time so you can help get some cost savings and be able to work together on solving these problems?’ ”

That’s the kind of information new Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan says he’s waiting for.

Despite a state-appointed emergency manager making all of the financial decisions for the city, Duggan vows to use what power he retains to make Detroit a more attractive place to live, beginning by bringing anti-blight agencies under a single Land Bank Authority.

But the mayor says he needs the information from the mapping database to improve Detroit beyond its thriving downtown and midtown areas.

“Everything starts with the neighborhoods,” Duggan says. “And so we’re going to build a legal team at the Land Bank to do what I was doing when I was in the prosecutor’s office: with lawyers to go in and sue the owners of the abandoned houses, knock down the ones that can’t be fixed, sell the ones that can, and move through the city on a systematic basis.”

At least one decision already appears to have been made.

Remember the flooded basement inside the abandoned home in Brightmoor? Once abandoned homes are removed, water service will be turned off to those areas permanently.

9(MDA3MTA1NDEyMDEyOTkyNTU3NzQ2ZGYwZg004))