[Note: This is a revised edition of the memorial tribute I wrote for Max Roach after attending his funeral on August 24, 2007. It was published in the Daily Hampshire Gazette. Roach died nine years ago today.]

Max Roach’s funeral was held last Friday at The Riverside Church in New York City, eight days after his death on August 16 at age 83. It was scheduled from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. and it more than honored Max’s flawless sense of time for notwithstanding numerous tributes and musical interludes, it ended at 1:10 p.m. The church was filled to capacity with over 2000 in attendance and an overflow crowd outside on Riverside Drive.

In the week following his death, I’d dedicated much of my radio programming to his memory, and been interviewed by several reporters about his legacy. I first met Max in 1979, when I produced a concert by him in Worcester, Mass, and subsequently came to know him through a series of lively encounters over dinner and as his guest at concerts in New York. But it wasn’t until I drove to the funeral that I remembered just how central this jazz master was to my own life’s journey, and not only by his presence, but in one significant instance by his absence.

Roach became a Professor of Music at UMass in 1972, the same year that I was projected to enter college as a freshman. However, college was not in the cards for me at that time. I had a legacy of my own to deal with, that of a family-owned engineering business that I’d been told to prepare for from my earliest days in grade school. This was not to be, but in 1972 I was profoundly stuck between respecting my family’s wishes and honoring something that felt much truer to me, namely my love of jazz. No doubt about it, celebrating the music of Max and Miles and Monk and Mingus held a much greater sense of calling for me than running a transit. But as an 18-year-old, the path to the latter was much clearer than was turning a passion for jazz and a keen interest in its history into a career. So I put off college, made a stab at training as a civil engineer on the job, and continued my nightly jaunts to nightclubs, jam sessions, record stores, and anywhere else where one might glory in the sounds of modern jazz and blues.

This continued for a few years until the day when my cousin Tara who was attending UMass paid a visit. I was wearing out a new reissue of Charlie Parker’s Savoy recordings, and as we sat and listened to them, Tara made casual reference to the fact that Max Roach, the drummer with Parker’s trailblazing quintet in the forties, was on the faculty in Amherst. This came as a stunning revelation, a “Go West” moment, and in no time I began to envision a course of study that didn’t involve plane geometry. When I began hinting around the office that I’d discovered a new beacon in Amherst, the jazz great Max Roach, my father and uncle, who’d never heard of him, looked at me aghast. But over their protestations and warnings that I was embarking on a course of little promise, I enrolled at the University the following semester, eager to read the classics and study jazz history with Professor Roach.

As it happened, Max had begun a sabbatical the semester I arrived in Amherst– and thereafter, he maintained a largely adjunct status with the campus, one highlighted by his annual appearances at Jazz in July and his solo hi-hat tribute to Count Basie’s great drummer, “Papa Jo” Jones. Whether it was an oversight of the university’s bureaucracy that kept Max’s name in the course catalogue or my lack of diligence, I learned of his absence only after attending the first meeting of Jazz History 201. There we were greeted by Max’s sub, an excellent saxophonist who pulled me aside after our first meeting and asked if I’d be willing to help him teach the class? I leapt at this informal arrangement, and over the course of the semester discovered a new purpose in my life. I had Professor Roach’s absence to thank for the opportunity.

It would remain another couple of years before I actually met Max, and by then I was hosting jazz radio programs at WCUW in Worcester, writing a regular music column for the local weekly, and helping to produce a concert series under the auspices of the radio station. When I brought him to Worcester for what proved to be the first solo percussion concert of his career, it marked the beginning of a substantial new friendship in which Max served as an inspiring mentor.

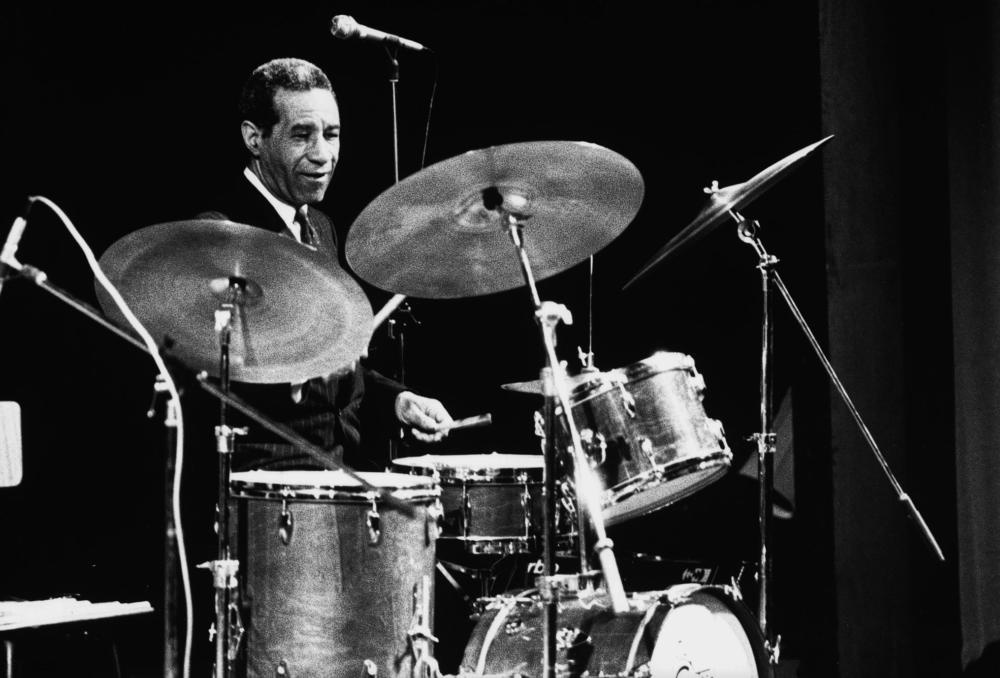

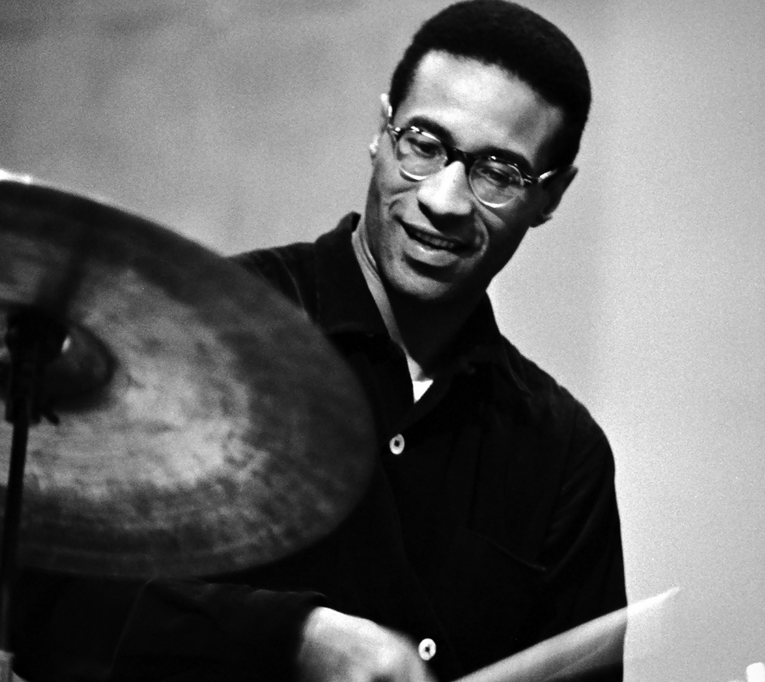

I was hardly alone in having my life shaped by Max Roach. As was abundantly clear by the presence of over 2000 people at his funeral (among those I recognized were Sonny Rollins, Roy Haynes, Cicely Tyson, Chico Hamilton, Odeon Pope, Avery Sharpe, Fred Tillis, Yusef Lateef, Sheila Jordan, Harold Mabern, Rufus Reid, Steve Turre, and former New York Mayor David Dinkins), Max served as a mentor, role model, and teacher to many over the course his long career. In league with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Bud Powell, he came to prominence as an innovator of modern jazz, and he may be the most influential drummer of all time. To watch Max play the trap drum set, which he preferred calling a “multiple percussion unit,” was to behold a marvel of human agility and inventiveness.

Moreover, Roach was in the vanguard of a new social consciousness, one reflected in his powerful music. Albums such as We Insist: The Freedom Now Suite, Percussion Bittersweet, Lift Every Voice, and Sonny Rollins’s Freedom Suite, were bold declarations against segregation in the U.S. and apartheid in South Africa, and celebrations of independence movements in Africa. As a tireless advocate of jazz as an art form, he played a major role in the establishment of the African-American Music major at UMass, and in the growing prestige that jazz enjoys at cultural institutions like Jazz at Lincoln Center and the NEA. Congressman Charlie Rangel read a letter by Bill Clinton at the funeral in which the former President praised Roach for “aligning” his music with the civil rights movement and “promoting ideals of equality and justice.”

Additional speakers included Maya Angelou, Amiri Baraka, Lt. Gov. David Paterson, Bill Cosby, Stanley Crouch, Sonia Sanchez, Phil Schaap, and the Rev. Dr. James Forbes, whose invocation suggested that Max had “modulated from time to eternity.” The Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts III, pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, gave the eulogy. These were interspersed with music by trios featuring Cecil Bridgewater, Billy Harper, and Reggie Workman; Gary Bartz, Harper and Workman; Cassandra Wilson, Bridgewater, and Tyrone Brown; and solos by Randy Weston, Billy Taylor, and Jimmy Heath, who played “There’ll Never Be Another You” on soprano saxophone. Wilson sang “Take Me Back Where I Belong,” and the soprano Elvira Green sang “City Called Heaven” and “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” Max’s drum stool and hi-hat were placed prominently on the altar; as the surest sign of respect, no other drummers played during the funeral.

The speakers wove elements of humor, awe and poignance in their tributes. Angelou described Max as “dedicated, disciplined, and daring.” Baraka and Sanchez testified to his musical genius and political courage in bold, staccato verse. Baraka’s poem called the names of numerous drummers who are in Max’s debt, and Sanchez riffed on how beautifully he embodied the name Max. Paterson placed him in a lineage of black heroes including Harriet Tubman, Paul Robeson, and Malcolm X.

Bill Cosby paid tongue-in-cheek tribute to Max as the man who made him become a comic. Initially, Cosby had wanted to be a drummer. He’d spent $75 for a basic kit, and he gained a sense of how certain things were done from seeing Vernell Fournier and Art Blakey, but once he saw Max, he gave up in frustration. Later, when he’d become famous and finally met Roach, he said, “You owe me $75!” Cosby recounted how impressed he and his homeboys from the Philly projects were with Max’s sartorial elegance. When they spotted him wearing a blue blazer with a crest, one of them said, “Max must have a boat!” He also noted that “Brooks Brothers must have sold a ton of suits” once Max and Miles and other jazzmen adopted a buttoned-down look in the fifties.

Phil Schaap talked about Max as a man of sensitivity and strength. Of the special interest that many jazz musicians have in boxing, he noted that Max related it to power. Schaap, the jazz radio legend of WKCR in New York, and a close personal friend of Max’s, said that when they listened to records together these past few years, Max would often ask for “Strong Man,” the Oscar Brown, Jr. song he recorded with Abbey Lincoln in 1959. (I often thought of Max as Oscar’s model.) Schaap also described the wounds that Max carried through the years, of racism and widespread Klan terror in the decade of Max’s birth in North Carolina; the early death of Max’s only brother; and the devastating deaths of trumpeter Clifford Brown at age 25 in 1956, and of his great discovery Booker Little at 23 in 1961.

In his eulogy, the Rev. Butts invoked “The Holy Ghost” as a likely source of Max’s extraordinary musicianship and a sense of “righteous indignation” as a guiding force of his activism. Butts closed with the words from “When the Saints Go Marching In,” voicing certainty that Max was now “in that number.”