Charles Cajori, who died on December 1 at the age of 92, was one of the last of what constituted the second generation of Abstract Expressionist artists. Born in Palo Alto in 1921, grandson of the renowned Swiss mathematician Florian Cajori, Charles grew up on Philadelphia’s Main Line and studied at the Colorado Springs Art Center and Cleveland Art School before joining the Air Force in 1942. Four years later, he enrolled at Columbia on the GI Bill and soon realized that the post-WWII art world was becoming centered in Lower Manhattan.

Cajori became a denizen of the 10th Street art scene. He befriended Franz Kline and Willem DeKooning, hung out at the Cedar Tavern, and rented a $15 per month studio where he devoted himself to drawing and painting. In 1952, he was a co-founder with Lois Dodd and others of the Tanager Gallery, one of the first artist-run co-operatives in New York. A decade later, Cajori was among the charter members of the faculty of the New York Studio School where his colleagues included Philip Guston, Louis Finkelstein, and founder Mercedes Matter. He remained active as a teacher at the West 8th Street establishment until last year. He was also on the faculty at Queens College for many years beginning in 1965.

![Cajori Imagined Landscape II [1956]](https://digital.nepr.net/music/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/03/Cajori-Imagined-Landscape-II-1956-e1493051806945.jpg)

Like his friend and colleague Leland Bell, who made the painterly observation that saxophonist Lester Young’s style “respected a rhythm of angles,” seeing Lester with Count Basie in the late 30’s was a touchstone for Cajori. And just as the art world’s center shifted from Paris to New York in the late 40’s, the jazz scene was undergoing a change in locus from 52nd Street to Lower Manhattan at the same time. In New York terms, Harlem remained the music’s mythical home, but the creative currents were surging in Greenwich Village and Lower East Side venues like the Village Vanguard, Half Note, Village Gate, Slug’s, and the Five Spot. During its heyday in the late 50’s, the Five Spot was like a second home for Cajori, who could recall with vivid detail nights spent listening to Monk’s Quartet with John Coltrane, Billie Holiday with Mal Waldron, Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, and Lennie Tristano over 37-cent beers. (The interview at bottom with Cajori and sculptor Tom Doyle underscores the purchasing power of pennies a half century ago.) During Monk’s long residency at the Five Spot in 1957, a flyer for one of Cajori’s shows at the Tanager could be seen above the pianist’s chapeau-topped head.

In a 2002 interview with art historian Jennifer Samet, Cajori discussed a block of black paint that he’d removed from his painting, “The Game,” because he saw it as an obstacle to the rhythm of the piece.

![The Game [1990-2000]](https://digital.nepr.net/music/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/03/Cajori-The-Game-1990-2000.jpg)

John Goodrich’s eulogy in artcritical began by noting that Cajori was not only an accomplished and acclaimed artist, “but extraordinarily generous and accessible as well.” To this I can only add, “Amen.” I’ll long cherish the memory of conversations with Cajori, and in particular his curiosity about what inspired my passion for jazz and interest in art. Cajori was a truly avuncular presence in my life, as he was for many others. As art and music are fields that many feel a calling toward early in life, both disciplines bring young people into the realm of the elders as teachers, mentors, and guiding lights. That’s a great responsibility for the masters, one requiring patience, openness, and trustworthiness. Cajori was well-suited to these imperatives.

A testimonial to this quality in Cajori came in the form of a letter that Bill Frisell addressed to him about a decade ago. The guitarist, who grew up in Denver, recalled an encounter with Cajori when he was in his early teens. Cajori’s father and Frisell’s father were colleagues at the Colorado Medical School. Bill remembered fondly the kindly attention that Cajori paid him on a visit to the Frisell home, and in particular that he’d brought along records by Monk, whom he was then unfamiliar with. As the years went on, Frisell often reflected on what a formative experience this was, and one day he used the internet to see if he could find a trace of Cajori. He found him, of course, and that occasioned the letter, which he hand-delivered to the Studio School. As it happened, Cajori had seen Frisell on a few occasions at the Vanguard with Lovano and Paul Motian, but he didn’t remember him as the kid he’d encouraged 40 years earlier. On Bill’s next trip to New York, they met for the first of what proved to be several get-togethers.

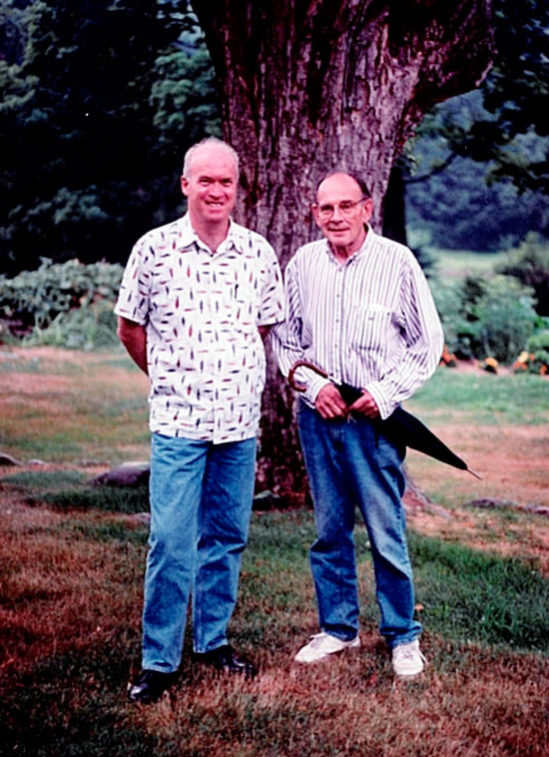

And here’s a delightful conversation between Cajori and the sculptor Tom Doyle in which they recall seeing Lady Day at the Five Spot; outsmarting the gas meter; the vicissitudes of making art; and DeKooning’s take on a Bowery bum’s adroit negotiation of space.

A memorial for Cajori is being held at the New York Studio School on Sunday, March 9, at 4 p.m. I’m honored to have been asked to be one of the speakers at the gathering celebrating the life and legacy of a man whom I was grateful to know as wise and principled, a wonderfully wry and humorous friend and mentor.

[…] noted on this blog in March that Frisell was inspired by, and dedicated a composition to the artist Charles Cajori, […]