Extra! Extra! Hot off the YouTube press, a slice of blues history on film that I’d never caught the slightest hint of, but here for all the world to see is color footage of Sonny Boy Williamson and Robert Jr. Lockwood doing their thing for King Biscuit Flour. It’s video only, no sound, and only 2:12 in length, but it’s vivid enough to transport you into the sun-drenched world of these legendary bluesmen as they play before a throng of locals in front of the Highland Lake Store outside Helena, Arkansas in 1942.

As a singer, harmonica player, and songwriter, Williamson fashioned a persona as a roguish, good-time-Charlie and griot-like town crier. In songs like “Pontiac Blues,” “Eyesight to the Blind,” “Sonny Boy’s Christmas Blues,” and “The Goat,” he depicted life in the Mississippi Delta and offered a wizened perspective on the wages of living outside the conventional bounds of hearth and home, of entanglements with multiple girlfriends who lived “Too Close Together,” and of double-crosses that reduced him to “Fattening Frogs for Snakes.” Williamson was among the most poetic of bluesmen, the composer of several dozen songs that drew remarkably less on the “floating verses” of the blues than on his own highly original constructions.

Lockwood, a stepson of Robert Johnson, was most likely the first musician in the Delta to play electric guitar. Born in 1915 in Marvell, Arkansas, his tastes ran to Count Basie, Charlie Christian and Lester Young, and he developed a combined single-string and chordal attack that became the prototype for backing Williamson and other harp players, especially Little Walter, with whom he recorded extensively in the 1950’s. His rapid strumming in the film suggests they might be playing something like Sonny Boy’s “West Memphis Blues.” Lockwood was already established in Chicago by 1941, and in that year recorded “Take a Little Walk With Me,” which may have been an unrecorded Robert Johnson original. But as he told Robert Palmer, author of the essential chronicle Deep Blues, “When I got back to Helena…I was walkin’ on Elm Street when Sonny Boy spotted me. He grabbed me, had me up off the ground, and said ‘You ain’t gonna leave here.’ And I was stuck with him for about two years.”

With Lockwood in tow, Williamson persuaded KFFA radio’s owner, Sam Anderson, to give them a 15-minute time slot in exchange for the opportunity to promote where they were working at night. Anderson found a sponsor in King Biscuit Flour, and the mid-day show made its premier on November 21, 1941. King Biscuit Time’s theme featured Sonny Boy singing a four-chorus blues in praise of the flour (“Everytime you look across the table, I’m reachin’ in the pan again.”) and the show quickly established the combo as a popular attraction in the Delta. Lockwood told Palmer they made as much as $75 each per night in the early ’40’s, a time when “most of the people who had good jobs was makin’ forty-five dollars a week.” With these earnings, the career-minded Robert Jr. became the owner of a 1939 Pontiac that he described as “all psyched-up. It was super fast.” Williamson, on the other hand, lavished money on whiskey, women, tailored suits, and craps, but what glorious music he made of these indulgences and (mis)adventures.

The Interstate Grocery Company, maker of King Biscuit Flour, capitalized on the show’s success by marketing a Sonny Boy Corn Meal and outfitting the pair in yellow shirts which they appear to be wearing in the film. Lockwood eventually moved back to Chicago (and for many years resided in Cleveland), and by the mid-’50’s Sonny Boy and his wife Mattie were living in Milwaukee, but area bluesmen James “Peck” Curtis, Joe Willie Wilkins, and Robert “Dudlow” Taylor kept the show going with live music well into the ’60’s, and they’re probably the group backing Williamson in the 1952 footage seen in the final 27 seconds of the film. Here’s what the show sounds like today with disc jockey SonnyPayne, who began hosting the show in 1951, spinning his favorite blues records.

Sonny Boy returned to Helena in the early ’60’s, and in between the several tours he made of Europe and England at the time, he made occasional King Biscuit appearances before his death in May 1965. Here’s how Peck Curtis remembers discovering his deceased friend, a man whom many considered ornery and Eric Clapton described as almost cruelly indifferent to the aspirations of young English musicians (“They want to play the blues so bad, and they play ’em so bad,” was Williamson’s blunt assessment.), but Curtis eulogizes him as “a great guy, my great manager.” Here’s Peck’s friend going it alone in Denmark on this spellbinding 1964 performance of “Lonesome Cabin.”

Chris Strachwitz, the German-born founder of Arhoolie Records who took the Helena location photo above, taped one of these King Biscuit broadcasts for release on a collection that’s otherwise devoted to Sonny Boy’s 1951 debut recordings for Trumpet Records. On Elmore James’s Trumpet classic, “Dust My Broom,” Williamson blows behind the great bottleneck guitarist, who was also a King Biscuit veteran. Levon Helm hailed from Helena, and Peck Curtis was one of his early models as a drummer. In Martin Scorcese’s film of The Band’s farewell concert, The Last Waltz, Helm and Robbie Robertson relate a poignant story about hanging out with Williamson when they were passing through the area. Here’s Robertson with a recollection of the encounter.

As for this film, there’s a kind of Holy Grail aura to its rarity that propels me to watch it again and again. In 1957, when Williamson was recording “Keep Your Hand Out of My Pocket” for Chess Records in Chicago, he warned Leonard Chess, “You better cut it while it’s hot, ’cause if it cools godammit it won’t be worth a damn.” That’ll never be said for Sonny Boy’s music, but I’d advise you to view this footage while it’s hot just in case it disappears as unexpectedly as it appeared last week on the net.

Two Sonny Boy Williamsons

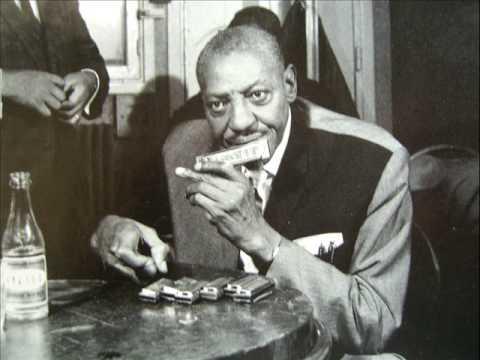

The Sonny Boy Williamson described here was the second bluesman of that name to make records. The first, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson (above right), was born in Jackson, Tennessee in 1914 and through his prolific series of recordings for Bluebird Records, he became the first major harmonica stylist of the pre-WWII era. He also composed numerous blues standards, “Good Morning [Little] Schoolgirl” and “Hoodoo Man Blues” among them, but at the height of his popularity in 1948 he was murdered in a Chicago street robbery.

The Sonny Boy of King Biscuit fame adamantly claimed to have been the “Original Mr. Sonny Boy Williamson,” but Trumpet Records historian Marc Ryan says it’s probably the case that Interstate Grocery’s owner, Max Moore, the emcee in the film, encouraged him to exploit the popularity of the name by adopting it at the inception of King Biscuit Time. Ironically, while this Sonny Boy may have traded on the other’s moniker, his harmonica playing and repertoire show hardly a trace of John Lee’s influence.

Sonny Boy’s given name was Alex “Rice” Miller, his birthplace was the Sara Jones Plantation in Tallahatchie County, MS, and his birth year was variously reported as 1894, 1897, and 1909. While he often boasted that he was “a 19th Century Man,” his sisters maintained that he was born on March 11, 1908. Beyond these convoluted details, what’s most likely is that by the late ’20’s Alex Miller was a professional billing himself as “Little Boy Blue” and “Harmonica-Blowin’ Slim;” what this 1937 photo (above left) makes indisputable is the pride he took both in his sartorial flair and in the instrument that would carry him from the Delta to international renown.

(Dedicated to the memory of Charlie Weiner, professor emeritus of the history of science and technology at MIT, and a lover of jazz and blues. Charlie died on January 28, 2012, at the age of 80.)

[…] Rogers scored a handful of r&b hits in the fifties including “That’s All Right,” “Ludella,” “Sloppy Drunk,” “Chicago Bound,” and “Money, Marbles, and Chalk.” But his place in blues history is forever secure through his charter membership in the combo that Waters put together in the late-forties. Muddy’s four-piece group, respectfully known as the Headhunters for the fierce drive they had for toppling other blues acts, is credited with electrifying the blues and establishing the sound that became a prototype for rock. But again, to Rogers’s credit, he tells O’Brien that it was really Lockwood and Williamson (Rogers, like many of his peers, calls him “Williams”), not Muddy and himself, who were responsible for amplifying the blues as early as “1940, ’41.” Has show business ever known a more selfless act of deflecting credit, especially before an audience that wouldn’t have known the difference? (Read an earlier blog I wrote on Williamson and Lockwood here.) […]