Next week, Massachusetts voters will consider a ballot question to increase the number of charter schools in the state. The fight over the proposal has been contentious, with the battle lines clearly drawn between proponents of charters and of traditional public schools. But there’s an experiment under way in Springfield, which could be a new model in public education. It’s called an empowerment zone.

The idea was born in 2014, when three middle schools in Springfield were failing. Student test scores placed them in the bottom one percent statewide. The schools were facing the possibility of Level 5 status, meaning the state could take them over.

That’s when the Springfield superintendent got a call from Chris Gabrieli, the head of the state’s Board of Higher Education, who’s also with a Boston-based non-profit called Empower Schools. He proposed placing the three schools — along were three others that also were struggling — into a special zone.

“I think at the core of the Empowerment Zone, it’s about giving educators in the building — the principal and the teachers — as much freedom as possible, to let them make choices about the team, the curriculum, the schedule,” Gabrieli said.

Gabrieli’s pitch wasn’t a hard sell for Springfield Superintendent Daniel Warwick.

“We had tried everything we could do to turn these schools around using traditional interventions and models,” Warwick said. “I was a long-term principal and as a principal, I loved autonomy to do what I need to do, and superintendents gave me autonomy because I was able to get great results.”

The teachers union also had to be brought on board. Tim Collins, head of the Springfield Education Association, said that Mitchell Chester, the state education commissioner, “sort of made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.”

“It was, send some schools into level 5 — which means they’d lose their collective bargaining rights, they’d all have to reapply for their jobs — or try this experiment: the Empowerment Zone,” Collins recalled.

The state denies that the choice was presented that starkly, but agrees that the schools could have been taken over if there wasn’t improvement.

The impact of the Empowerment Zone, which is going into its second full year, can be seen at places like Springfield’s Duggan Academy, a middle school which also has about 70 high school students. At Duggan, 70 percent of sixth graders read below grade level.

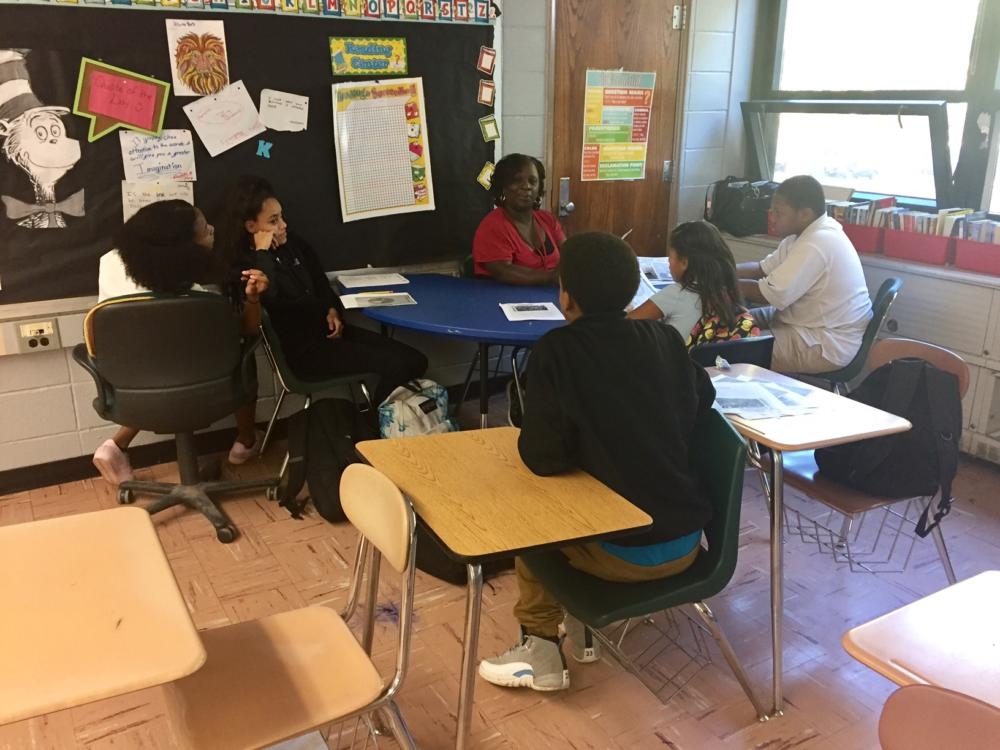

On a recent morning, seventh graders there were engaged in an English class. But it wasn’t 30 students staring into space as a teacher drones on. Instead, it was four boys and girls reading a book under the watchful eye of a teacher. On the other side of the room, five students were reading at a higher level with a teacher’s aide.

Mike Calvanese is principal of Duggan Academy. He said he got the idea for the program when he visited a high-performing charter school in Lynn last June.

“They had every kid at a reading level reading with a teacher and not just looking at a book,” Calvanese said. “They were reading the book, helping sounding out the words, working out the words that they didn’t know and it was exactly what we needed.”

According to Calvanese, getting such a reading program implemented at a traditional public school would be far different.

“You’d have to go through some approval process and see if there’s funding available for it,” he said. “But it would take awhile, I mean it would take a year. To do something in late June and then have it ready to rock in August, that takes autonomy and that’s what we had.”

Calvanese has used his control of a $6.5 million budget to lengthen the school day, try to foster a positive school culture by creating a dean of culture position, and allow more time for music and art. Unlike regular public school principals in Springfield, he also gets to choose what services — like the math curriculum — to buy from the district. That leaves him with money to pay teachers more.

“That has helped out tremendously with recruitment,” he said. “Local charter schools may not be quite up to the pay scale that our schools are at — public schools as well, not just charters.”

The test results for the first full year of the Empowerment Zone came in last month. Duggan showed solid improvement. The other schools are more of a mixed bag, with some scores up and some down.

Gabrieli said turning around schools is a multiyear process. He’s confident the zone will prove itself in time, especially as the debate over traditional schools versus charters rages on.

“The first way was districts. They go back in Massachusetts to the colonial times, obviously,” he said. “More recently, in the last 20 years, we’ve had charters in lots of places and one big difference is that charters have a lot of autonomy at the school level and that’s something we think is great, but the districts remain the places where, you know, the democratic voice is strongest and where all the students are served. So the [Empowerment] Zone is a third way.”

According to Gabrieli, the public education world is watching.

“I get the chance to go around the country, and I can’t tell you how many people are excited to hear about what’s going on in Springfield, and Springfield is a city of firsts so why not this?” he said.

Two weeks ago, the Springfield School Committee voted to add the city’s High School of Commerce and its 1260 students to the Empowerment Zone, and New Bedford is now exploring the possibility of placing all its middle schools in a similar zone.