It’s a luxury afforded by YouTube that we can enjoy historic performances like Howlin’ Wolf on Shindig! without leaving the comfort of our homes. 25 years ago, when I first saw this amazing footage, that wasn’t the case. In October 1991, I learned that the Shindig! clip was going to be screened at the Henry Street Settlement House in New York. I’d seen an excerpt of the performance in the otherwise forgettable documentary 25×5: The Continuing Adventures of the Rolling Stones. A friend owned a VHS tape of it, and every time I stopped by I’d ask him to cue up the scene with Wolf. But the excerpt was terribly brief, so when I learned that the entire four-minute clip was going to be screened in New York, I beat a quick path to the city. As it happened, the footage flew by on the big screen at Henry Street, but it was followed by Wolf’s former sidemen Hubert Sumlin, Henry Gray, Eddie Shaw, Calvin Jones, and S.P. Leary playing “Smokestack Lightning,” “I Ain’t Superstitious,” “Shake for Me,” “Howlin’ for My Darlin’,” and other Wolf classics. Notwithstanding some bickering between Sumlin and Gray, seeing these alums was an unanticipated bonus that made the schlep worthwhile, with one significant caveat.

I’d attended the event with three friends and a seven-month-old baby boy. We’d spent that beautiful fall day walking dozens of blocks down to the Lower East Side, and later left Henry Street (why the settlement house was the host site is beyond me) buoyed by Wolf’s music and the ease of catching the A Train to digs in Washington Heights. However, as the subway got further uptown, it began to empty out of passengers, and just like that we became sitting ducks for two jittery guys who jumped on at 135th Street, brandished a gun, and demanded “cash and rings and watches.” Thankfully, that and a few beads of sweat was all we lost, but the threat they presented as nervous muggers facing off against a party with an infant is something we’ll never forget. I’d stared down the barrels of a couple of other pistols by that time and escaped unharmed, and while that may have helped me remain calm during the hold-up, PTSD set in by the following morning. It would keep me away from the city for nearly a year.

13 years later, in 2004, a visit I paid to Chicago coincided with an exhibit called Sweet Home Chicago: Big City Blues 1946-1966 that was on view at the Museum of Science & Industry near the University of Chicago. (The Hyde Park museum, which was built for the 1893 Colombian Exposition, is where the Butterfield Blues Band’s East West album cover photo was shot.) The exhibit consisted of individual kiosks devoted to 25 major figures in blues, from Dinah Washington, Muddy Waters, and Eddie Boyd to Junior Wells, Otis Rush, and Magic Sam. For this blues lover, it was the equal of a major retrospective on Cezanne or Picasso. Each kiosk was loaded with photographs, posters, handbills, and other memorabilia for each artist, including Paul Butterfield’s passport; the sales receipt for Little Walter’s sweater from Goldblatt’s, the department store immortalized in Billy Boy Arnold’s “I Ain’t Got You;” guitars played by Tampa Red, John Lee Hooker, Robert Nighthawk, and Buddy Guy; a coffee-stained envelope on which Charlie Musselwhite had jotted down the lyrics to “Help Me” in preparation for his first album, Stand Back; and and much to my surprise, the AFTRA application that Howlin’ Wolf (as “Chester Burnett”) had filled out in pencil for his appearance on Shindig!

Wolf was born Chester Arthur Burnett on June 10, 1910, in West Point, Mississippi. He was in his early forties when he made his first records for Sam Phillips in Memphis. Phillips, who discovered Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis, said later on that Wolf was the most arresting figure he ever saw play music, and that no one could transform existence more completely than Wolf in the span of two-and-a-half minutes. In Peter Guralnick’s recent biography, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock’n’Roll, Phillips says, “To see him on a session, it was just the greatest show. The fervor in that man’s face, his eyes rolling up into his head, sweat popping out all over…locked into telling you individually about his trials and tribulations. He’s the only artist I ever recorded that I wish I could have had a camera on. The vitality of that man was something else!”

As it happened, Wolf was nearly 55, but as vital as Sam Phillips could have wished, when he pulled out all the stops for his May 20, 1965 appearance on Shindig! The Rolling Stones, who’d enjoyed a #1 hit in England with their cover of Wolf’s “Little Red Rooster,” agreed to appear on the show– it was the band’s second appearance on American television; they’re first was on the Hollywood Palace– only if Wolf or Muddy Waters were also booked. Wolf was available, and he made the most of it; indeed, for a select group of viewers, his finger-wagging, tail-shaking, harmonica-wailing performance of “How Many More Years” ranks as one of the greatest moments in television history. Peter Guralnick, quoted in the 2014 biography, Brian Jones: The Making of the Rolling Stones, says, “I’ve listed it as one of the Top Ten TV moments of all time, one of the most significant moments in cultural history– part of a wonderful movement that couldn’t be turned back.” Jones’s biographer Paul Trynka writes that the Stones founder “thus engineered an event that fulfilled just about every ambition of his twenty-three-year-old life.” And in Jones’s bio, Buddy Guy says it “broke through a boundary line that no one thought could be crossed.”

On the day of the taping, Son House, who’d been rediscovered a year earlier, was in Los Angeles for concerts at UCLA. His manager Dick Waterman got a tip on the taping and made arrangements to bring Son to the studio. At the 2015 Son House Festival in Rochester, New York, Waterman recalled that Wolf was seated when they arrived but the instant he saw House, he unfurled his 6’4″ frame from a cramped auditorium seat, “like an elephant in a phone booth.” From around 1930 until the time he was inducted into the U.S. Army in 1941, Wolf divided his time between farming and playing music. Important contacts included Charley Patton and Rice Miller (Sonny Boy Williamson II), and in the late thirties, he found himself continually running into Son House and Willie Brown at “Saturday night hops” around the Delta. He occasionally joined the duo on “fast numbers to dance to…”

In Moanin’ At Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin’ Wolf, a richly anecdotal biography by James Segrest and Mark Hoffman, Wolf is quoted as saying that Brown was the more capable guitarist with a knowledge of chords and the ability to “finger” notes. Unlike House, “He didn’t have to play everything “in open chords” or with “that bottleneck thing,” but Son was the more compelling performer. In one of the interviews House gave after his rediscovery, he remembered seeing Wolf playing electric guitar and a rack harmonica on the streets of Robinsonville, Mississippi in 1938. He also noted that they dated sisters for awhile, and Waterman says that when they reconnected at the Shindig! taping, the sisters were still on their minds. After witnessing their reunion, Brian Jones asked Waterman the identity of the man who’d commanded Wolf’s attention. When told it was Son House, Jones replied, “Oh, the man who taught Robert Johnson.”

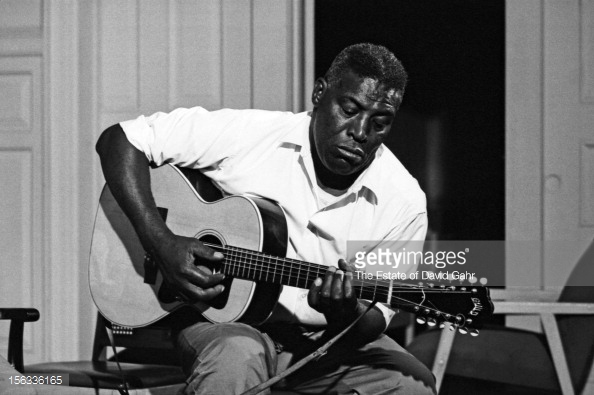

For the taping, Wolf was accompanied by the Shindogs, a house band that on this occasion included James Burton on guitar, Joey Cooper on bass, Chuck Blackwell on drums, and the 18-year-old Billy Preston at the piano. As seen in the clip, Shindig! host Jack Good halts the overeager band in order to ask Jones about their special guest. After acknowledging Wolf as the Stones’ idol, Jones’s brusque interruption of Mick Jagger feels like a acrimonious non sequitur, but it was apparently typical of the discord between the band’s founder and its teen idol frontman. The Stones eventually developed a sustained rapport with Muddy Waters, but this was as close as they got to Wolf, who seized the moment for all it was worth, but was apparently unimpressed by all the hoopla. When the show aired a few nights later on ABC, he was at home in Chicago taking a nap before the night’s gig. His step-daughter Lillie alerted him to the broadcast, exclaiming “Wolf, wake up! You fixing to come on now.” Wolf turned over and said, “Yeah, I done seen that before,” and continued to snooze.

A year after their Shindig! encounter, Wolf and Son House were seen together in a film made by Alan Lomax on a soundstage at the 1966 Newport Folk Festival. Wolf was in outstanding form then too, but he wasn’t so reverent toward House, who was noticeably intoxicated. Here’s Wolf with his longtime guitarist Hubert Sumlin playing the Delta classic, “Dust My Broom.” Much like the Stones a year earlier, House, who’s seen on a bar stool in fedora and bow tie, responds like a youngster to the groove of the mighty Wolf.