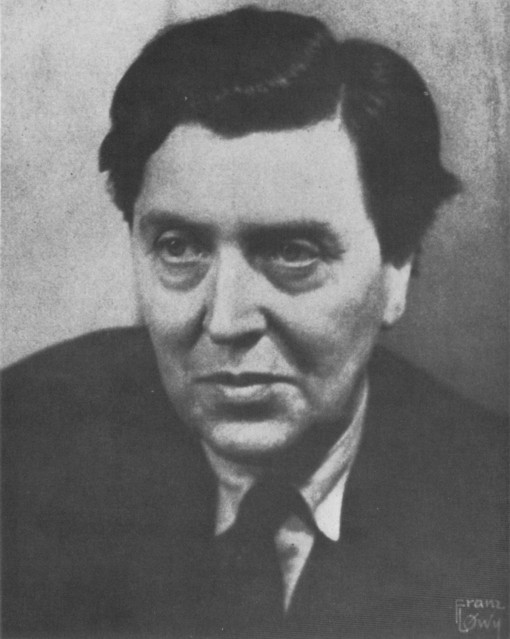

Of the many levels of appreciation I have for Dan Morgenstern, first and foremost is the ease with which this man born to a high Viennese cultural background embraced and understood jazz, the great American art of the highbrow and low. Dan was born 85 years ago today. No less a figure than the composer Alban Berg, a close family friend, presented young Daniel with a copy of Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik as a sixth birthday present. It was then that “this kind of music got through to me,” he wrote in the Introduction to the Morgenstern reader, Living with Jazz. “I loved this piece, soon knew it by heart, and was shaken by Berg’s sudden death just two months after he gave me this gift.”

This would not be the last unsettling experience of Dan’s youth. Hitler’s anticipated annexation of Vienna, “the city where he had learned to hate Jews,” led the Morgenstern family to flee in separate directions, his father Soma, a former cultural correspondent for a major German newspaper, to France, Dan and his mother to Copenhagen. It was there where he heard Fats Waller in concert, an experience that “fascinated” the ten-year-old who, notwithstanding the language barrier, delighted in Waller’s “enormous energy and good humor.” Waller records, and a few by Chick Webb with Ella Fitzgerald, became the cornerstone of his education in listening for the “nuances” of jazz. It’s an appreciation that soon grew to include the Mills Brothers, Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli (aka the Quintette of the Hot Club of France, which he also saw in concert), and Duke Ellington.

The eventual Nazi occupation of Copenhagen had the “unintended result” of jazz becoming “more popular than ever– a phenomenon universal to the countries under the Hitler jackboot.” (The same would later occur in the Soviet Bloc countries of Eastern Europe.) Thus Morgenstern gained an early understanding that “jazz stood for freedom, for democracy, and for the spirit of America…which seemed to embody hope for a better future.” When the Danish underground learned that the Nazis were about to round up all Jews for deportation, the Morgensterns were among the families spirited to safety in Sweden. There he attended a boarding school where one of his roommates was a jazz fan with a “distinguished stash of records.” One of these was “Bugle Call Rag” by an Eddie Condon assembled group with Red Allen, Pee Wee Russell, and Zutty Singleton. “Whoever woke up first would activate the turntable, and those swinging sounds would promptly dispatch any cobwebs. They were still lingering in my ear when on June 6, 1944, the morning’s first class was interrupted by the news of D-Day.” He spent the rest of that summer living in the home of a “hospitable, wealthy Swedish family” whose young son was a jazz fan with an already keen devotion to Benny Carter.

Morgenstern’s father had made his way to the U.S. in 1941, so with the war’s end, Dan knew it was only a matter of time before he and his mother would join him. In the meantime, back in Copenhagen, his “rather scattershot interest in jazz began to become a bit more directed,” and Duke Ellington became the first artist whose records he collected methodically. On April 22, 1947, Dan and his mother arrived in New York. On his first night there, he scanned the radio dial until he heard some jazz announced by a “disc jockey with the unlikely name of Symphony Sid.” He found Sid hard to understand, which also went for the version of “I Can’t Get Started” played by Dizzy Gillespie. Dan was already familiar with Bunny Berigan’s “triumphantly accented record” of the Vernon Duke song, but Gillespie’s struck him as “dirge-like, with an oddly mournful backdrop.” In retrospect, he called it “an appropriate introduction to jazz in 1947 New York.”

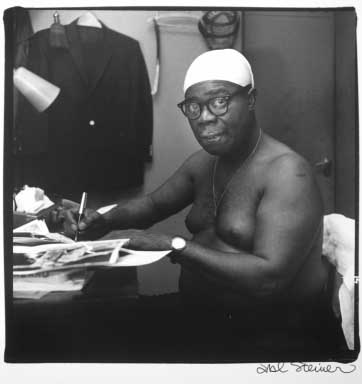

The 18-year-old Morgenstern soon made his way to 52nd Street and became immersed in the New York jazz world of midtown and Harlem. His first encounter with Louis Armstrong, “King Louis,” in Dan’s jazz firmament, took place in 1949 at the Roxy. He’d already befriended Jeann Failows, a “member of Armstrong’s inner circle [who] was entrusted with Louis’s voluminous fan mail from all over the world,” and she met him at the backstage entrance to the Roxy. He was escorted to Louis’s dressing room where, “wrapped in a white bathrobe, and that famous handkerchief tied around his head, he greeted us warmly.” After contemplating Morgenstern’s last name and Scandinavian background, Louis crowned him “Smorgasbord,” and called him that from then on. It was only the first of many meetings between the two, and for Dan “the magic never wore off.” 30 years later, when he was the editor of Down Beat, he devoted an entire issue to Armstrong’s 70th birthday, for which Pops paid him “the greatest compliment I ever got. He wrote, ‘I received the magazine and it knocked me on my ass!'”

Following military service, Dan studied at Brandeis between 1953-56, but not necessarily with the idea of becoming a jazz critic in mind. It was Armstrong who ultimately inspired that direction in his life. More precisely, it was the carping that so many other critics engaged in about Louis’s music and stage manner that drove him to write. “For me, reading stuff like the [John S.] Wilson piece [in The New York Times] and worse brought me closer and closer to finally deciding that I should write about jazz and become part of a breed from which I felt profoundly alienated.” Wilson, in this case reviewing a performance by the All-Stars in Brooklyn, wrote that it “scarcely seems proper to book Mr. Armstrong’s group in a jazz series…for [it’s] less a jazz band than an attraction.”

Morgenstern understood that “the barbs of critics” had little impact on Armstrong, who lived by the maxim, “A note or a good tune will always be appreciated if you play it right.” The same might be said of Dan, who has written good notes and tuneful essays for 60 years, and along the way served as editor of Metronome and Jazz, as well as Down Beat. He also piloted the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers for many years after becoming its director in 1976, and is one of the handful of non-players who’s been honored as an NEA Jazz Master.

Partly through his stewardship at Rutgers, the world of jazz scholarship has grown immensely over the past 40 years, and much of that now appears between the covers of books. But for a couple of generations, the liner note essay was as essential as any tome for learning jazz history, the particulars of recordings, and the players who make them. Morgenstern is one of the greatest contributors to this cherished form of jazz writing, and his eight Grammy Awards are a measure of the distinction he enjoys. For Dan, the driving force behind his aesthetic has been his personal relationships with musicians. “What has served me best, ” he says, “is that I learned about the music not from books but from the people who created it.” In other words, Dan hangs out, and I can’t think of another writer of jazz criticism who is so widely respected and beloved.

What’s inspired this reflection on Morgenstern is the following excerpt from a piece he wrote in Armstrong’s honor for the 70th birthday issue of Down Beat. Ricky Riccardi posted it on Facebook this week in anticipation of Dan’s birthday, an occasion marked every year at Birdland during David Ostwald and the Gully Low Jazz Band’s weekly celebration of Armstrong’s music. Riccardi is the author of an essential Armstrong volume, What a Wonderful World, The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. He’s also the archivist at the Armstrong House and Museum in Queens. Ricky wrote an essay on Morgenstern’s relationship with Armstrong for Current Research in Jazz, which you’ll find here.

“You will also find tributes from two leading jazz critics. Unlike the musicians, they circumscribe their praise with comments defining Louis ‘the entertainer’ as someone distinct from Louis ‘the artist.’ Only this confused century could have spawned a theory that views art and entertainment as incompatible. What artist worthy of the name does not first of all desire to communicate — to touch the hearts and minds of others? And is this not what Louis Armstrong does so supremely well? Trumpeter, singer, actor, entertainer, human being: all these are the one and only Louis Armstrong, a whole man. Long ago, Louis dedicated his life and art to a noble purpose. ‘It’s happiness to me to see people happy,’ he has said, and he has turned millions on with his smile, his voice, and his horn. Through thousands and thousands of one-night stands, on that hard old road, he has never given his public less than his best. Off stage, he has been just as generous. Louis was born with the knowledge that black is beautiful. Unmindful of fashions and trends, he has been true to himself and his heritage — a heritage he has enriched and transmuted to a degree not yet fully comprehended, and perhaps not fully comprehensible. All true art partakes of the mysterious. Louis Armstrong has always been in style, and always will be.” Dan Morgenstern, Down Beat, July 1970

I remember reading this when it first appeared, and together with George Frazier’s column for the Boston Globe that decried any notion of Armstrong as an Uncle Tom, it made for a deeply emotional experience that for this then 16-year-old was on a par with Louis’s music. It still reads that way, and reminds me also, in the aspect of “not yet fully comprehended” and “mysterious,” of Ralph Ellison’s symbolic use of Armstrong in his great novel, Invisible Man.

I couldn’t get to Birdland on Wednesday, so I asked Riccardi how Dan’s doing. He says,”When I tell you he’s not slowing down at all, believe me! 85 and he still lives in New Jersey but he must go into the city three or four nights a week, negotiating public transportation by himself, walking everywhere, just to catch all the gigs he can. And in case you missed this earlier today, he sang at the Satchmo Summerfest in New Orleans this past August and broke it up with his rendition of the Armstrong favorite, ‘You Rascal You’.”

That’s Riccardi at the piano and New Orleans radio personality Fred Kasten introducing Dan. Entertainment and art. Lowbrow and high. Like the music he honors with his prose, Dan Morgenstern integrates and embodies both. Enjoy!

[…] Morgenstern, the jazz historian whom I wrote about here a few weeks ago, saw the John Coltrane Quartet at the Half Note in the mid-Sixties. Lewis Porter […]